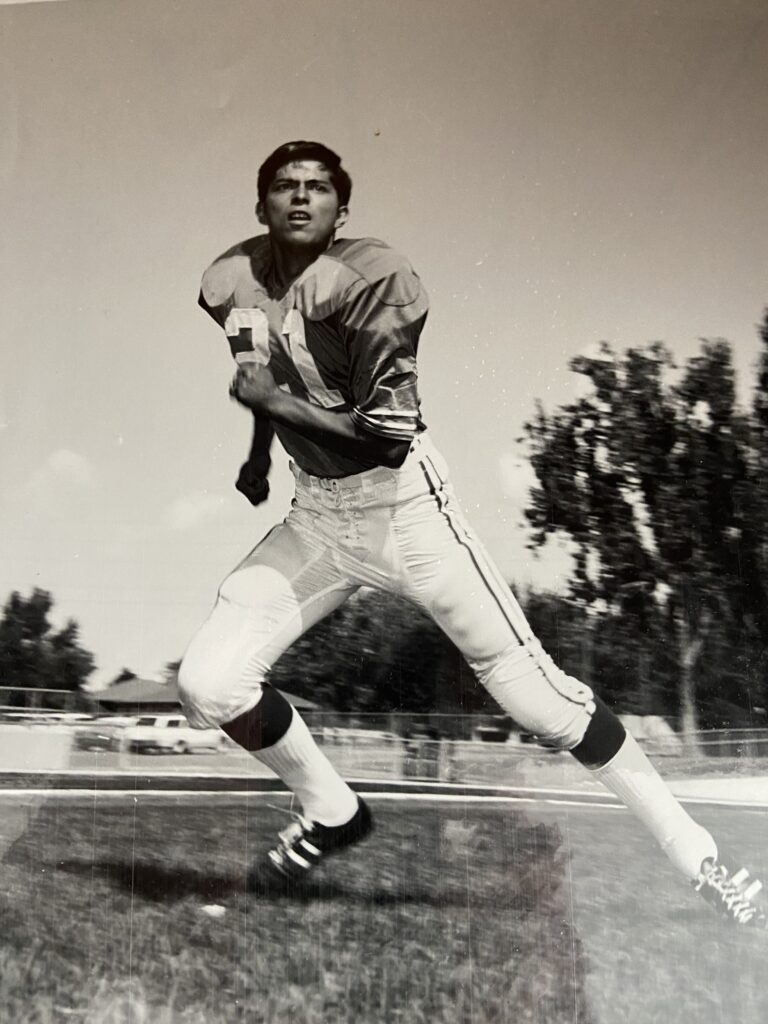

As a physical education major at Brigham Young University, Larry EchoHawk ('73) was finishing his degree while also completing his fourth year as a starting free safety on the football team, a role that had landed him a scholarship. He'd received a job offer in Blanding, Utah, and had not considered further education. Then his older brother, John, made a suggestion that changed EchoHawk's life.

"John came to me and said, 'You ought to go to law school. It will give you the power to change the lives of Native people and change laws,'" EchoHawk recalls. "At that time, less than a dozen Native Americans had ever obtained a law degree, so there was a great need."

The first graduate of the University of New Mexico's new law program for American Indians and the first Native American UNM Law School graduate, John was a trailblazer in Native law—and he wanted Larry to follow in his footsteps.

Taking an unexpected journey to law school

"The special law scholarship at the University of New Mexico was developed during the Civil Rights movement, when Congress was passing legislation to try to help minority racial communities be protected and develop their communities," EchoHawk says. "It continues to serve as a summer experience to help prepare Native students for the rigors of the first year of law school. They were recruiting Native students graduating in various fields who were not pre-law and not prepared, and it was a challenge to have them make it through."

After finishing the special scholarship in law (now called the Pre-Law Summer Institute for American Indians and Alaska Natives) like John did, EchoHawk decided he wanted to return to Utah for law school and applied "at the eleventh hour" at Utah Law.

"I didn't have the credentials a normal applicant would have. If I'd thought about law school, I would have prepared in undergrad," EchoHawk explains. "I met with the dean of admissions, Ron Harding, and he looked at my transcripts. I could tell he was about ready to say no, you're not prepared. I remember telling him, 'If you’ll admit me, you won’t be sorry. I know how to work.' Finally, the week before classes started, I was admitted."

Though the first year of law school was very difficult, EchoHawk says he improved semester by semester, spurred by the vision of what he would do to help Native Americans just like his brother had. After graduating, he moved to California to work, like John had, at California Indian Legal Services, helping impoverished Native people in the state. Two years later, he returned to Salt Lake City and opened a solo practice to help Native Americans in the area. As demand increased, EchoHawk soon hired another Native lawyer, Bill Thorne, at the practice.

Representing tribes on Idaho's Shoshone-Bannock Indian Reservation

However, EchoHawk's dream was to work as a tribal lawyer, but he didn't know any Native Americans in this field. In 1977, he applied for a contract for the largest Indian tribe in Idaho, the Shoshone-Bannock Fort Hall Indian Reservation.

"There were law firms out of D.C., Portland, Boise, and Salt Lake City, and it was just me. I went up to the reservation, and they had the general membership interviewing applicants. It was so unusual to see a Native American with a law degree that the tribal community selected me to be their lawyer instead of a large firm. They gave me a chance," EchoHawk recalls. "It was a fulfillment of my dream to be a lawyer working with tribal people and making an impact."

Five years into his service on the Shoshone-Bannock reservation, EchoHawk represented the tribe in the Idaho legislature during the Sagebrush Rebellion, a movement in western states to gain more state and local control over federal lands. Because the Shoshone-Bannock tribes had an 1868 treaty guaranteeing their right to hunt on federal land, the Sagebrush Rebellion would have taken away the tribe's vital treaty rights if it succeeded.

Making history in Idaho's state government

EchoHawk's experience in the state capitol helping to defeat one of the resolutions affecting treaty rights, along with a passion for improving education, inspired him to run for the Idaho House of Representatives.

"I had walked the streets of Pocatello and communities southward that summer talking to people on their doorsteps. Idaho was last in the nation in per-pupil expenditures, and my school district was near the bottom of 112 districts. I had been so greatly blessed by good education, which included the University of Utah law school, and I wanted that for my six children," EchoHawk says. "On Election Day in 1982, I won. The Pocatello newspaper called my election the 'shocker of southeast Idaho.'"

Though EchoHawk enjoyed representing the people in his district, he wanted to continue work for Native people, as the reservation was not included in his district. He sponsored a bill to create an Indian Affairs committee and educated the legislature about fundamental Indian law principles. Soon, he was sponsoring other bills that improved life for Native people in Idaho.

"When I first searched Idaho's statutory laws, there was not a single provision in Idaho code that was positive for Native Americans. The only thing I found was a negative law that empowered the state to take jurisdiction away from tribal communities," EchoHawk recalls. "I had the realization that my brother was right. Becoming a lawyer as a Native American would give you the power to change law, and that was what I was doing. I was making a difference in people's lives."

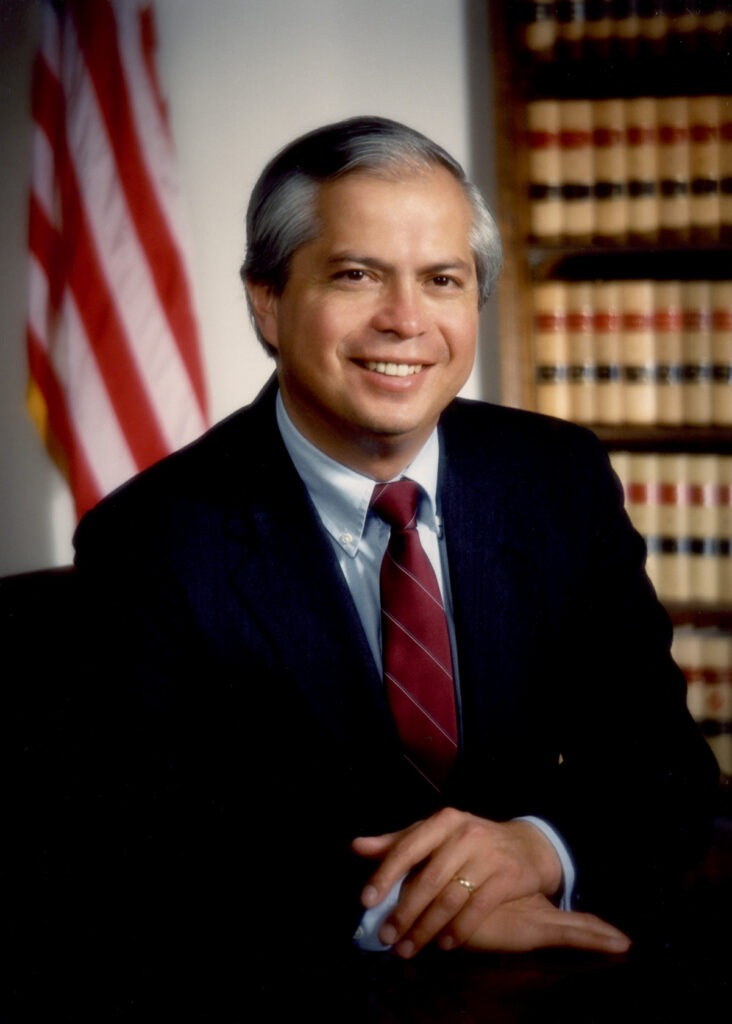

After two terms as state representative, EchoHawk served four years as Bannock County attorney. Governor Cecil Andrus then asked him to run for attorney general and promised to help with his election effort.

"Almost immediately after I filed my papers to become a candidate, I was somewhat deflated. The largest newspaper in Idaho published an article saying I had no chance because I had three strikes against me: I was a Mormon, an American Indian, and a democrat," EchoHawk says. "But another article said that if by some chance I could win, I would become the first American Indian in U.S. history to be elected to a statewide political office on a statewide basis. That kind of gave me a boost."

EchoHawk did win the election and says he was grateful to be part of American history, to again be involved in changing law, and to become the chief legal officer for Idaho. Four years later, Governor Andrus stepped down and EchoHawk ran for governor. Though polls suggested he would win, EchoHawk lost the election.

Pursuing a new teaching opportunity in Utah

The following morning, the dean of the BYU law school called, offered condolences on EchoHawk's election loss, and asked him to join the faculty there.

Initially, EchoHawk was hesitant. He didn't want to leave Idaho, and he wasn't sure about his next steps. After more discussion with BYU, he decided to work as visiting professor for a semester and teach a couple classes.

"Those are smart people there, because they admitted my son to law school. I felt I'd neglected him and missed a lot of his school activities when I was the attorney general and then running a campaign for governor," EchoHawk recalls. "When BYU offered me a full-time faculty position, I realized this would give my wife and I an opportunity to be with our son."

EchoHawk taught for 15 years at the J. Reuben Clark Law School—though he says that he "probably would have said yes to Utah Law if they'd asked"—when another Election Day changed his career trajectory.

Writing brighter chapters of American history in the presidential cabinet

"Just after the 2008 presidential election when President Barack Obama won, I was sitting in my law school office and got a phone call. The person identified himself as part of the presidential transition team and said he had an airline ticket for me. I said, 'I know you're looking for people to be part of the Obama administration, and I'm not going to leave Utah,'" EchoHawk says. "Then that person said, 'Would you give the next president the courtesy of a short interview in D.C.?' I thought, Well, if you put it that way."

After meeting with four people in D.C., EchoHawk returned to his hotel room and was getting ready for bed when he got another phone call.

"The voice on the line said, 'Your country is calling you into service.' It was a very emotional moment for me. I had volunteered in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War, and the same feeling came back to me," EchoHawk says. "He said, 'The President of the United States would like to nominate you to be assistant secretary in the Department of the Interior, the highest official in the U.S. government with full-time responsibility over Indian Affairs.' I remember thinking again, The power to change."

If EchoHawk agreed to the position, he would be the president's representative to 565 tribal nations, have a $2.5 billion budget, have authority over the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Education, and have 10,000 employees to help him fulfill that responsibility. When he got home to Utah, he pulled Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee from his shelf and read it again, noting the dark history of the treatment of Native people in the United States.

"I wanted to read it again because my concern was that I would be the face of the federal government in Indian country. I would want to do good things on behalf of Native people," EchoHawk recalls. "Finally, I said yes. It was one of the most satisfying roles I've ever had but the most difficult professional role. Most of the people in the 565 tribes live in poverty and had been treated unjustly. When I gave my first speech to 2,000 Native leaders, I remember telling them I would do everything within my power to do good things, to work with them to write brighter chapters of American history. We were able to accomplish great things."

Returning to Utah for church and government service

Though the Obama administration asked EchoHawk to serve a second term in the Department of the Interior, he received a call in 2012 to serve as a General Authority Seventy for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While in this role, EchoHawk often met with groups of Latter-day Saint Native Americans and spent two years living in the Philippines to oversee church operations there.

Shortly before he finished his church service in 2018, then-Gov. Gary Herbert asked him to serve as special counsel on Native American affairs.

"Gov. Herbert said, 'We have made mistakes in the state of Utah in our relations with the eight federally recognized tribes, and we need your help. We need to improve our relations, and we think you have the background to guide us,'" EchoHawk says. "I've been doing this for six years now, working with the governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general and advising them on major issues occurring with Native people. The power to change—to change the relations of one of the 50 states in the Union in their treatment of sovereign Native nations and Native people."

Earning the name EchoHawk

Throughout his career, EchoHawk has honored his Native Pawnee heritage and is proud to carry his great-grandfather's name, Echo Hawk.

"The elders had noticed that though he demonstrated bravery as a protector, he was a quiet young man—but others spoke of what he did. The elders said they heard the same words, that everyone spoke like an echo from one side, which is where echo comes from. The hawk is a symbol of bravery," EchoHawk explains. "He was pressured to give up his homelands when he was 19 years old and relocated to north-central Oklahoma. When he arrived, the military officer was taking a census. Echo Hawk didn't speak English, and he spoke his name in Pawnee. The officer told him they would give him an English name, and my great-grandfather said, 'I will keep my name, because I earned it.'"

One might say that Larry EchoHawk has earned his name as well—though he says he owes what has been a fulfilling life to the late admissions dean Ron Harding and to his brother, John EchoHawk.

"I think Harding made a difficult decision. I don’t know if there was an empty spot at the law school, but I was clearly not qualified like other students being admitted. He took a chance," EchoHawk says. "My brother John is a historic figure and was instrumental in creating what is known as the Native American Rights Fund, which protects the rights of Natives in courts and communities. They have changed the landscape of the rights of Native people. John was the first graduate of the special scholarship in law for American Indians, and now there are 3,000 Native lawyers. He was a pioneer clearing the way for others and inspired me to follow."

EchoHawk is also excited to see other Native lawyers in leadership positions, including Dean Elizabeth Kronk Warner.

"When I was admitted to law school in 1970, it was a class of 147 students and five of them were women. Now I stand before you in the presence of the second Native woman to ever be a law dean and the first-ever at University of Utah," EchoHawk said during his speech at the 2024 Utah Law convocation ceremony. "It makes me very proud to see that. She is a bright star."