Clinical Professor Jensie Anderson (’93) considers it an honor to have spent her career teaching and helping individuals access justice. Yet, growing up in Logan, Utah, she envisioned quite a different trajectory for herself. Her family was in the theatre business, so stepping out on stage was a natural fit for her.

Clinical Professor Jensie Anderson (’93) considers it an honor to have spent her career teaching and helping individuals access justice. Yet, growing up in Logan, Utah, she envisioned quite a different trajectory for herself. Her family was in the theatre business, so stepping out on stage was a natural fit for her.

“I started acting when I was very young, and all I ever wanted was to be an actress. I majored in theatre at the University of Washington, then came to the University of Utah for my last two years. I was accepted into the Actor Training Program and graduated with a BFA in theatre performance,” Anderson says.

Right after graduation, Anderson interned at the Alley Theatre in Houston, Texas, and then moved to New York, “which is what aspiring young actresses did in those days.”

“I waited tables, which is also what aspiring young actresses do. I worked at the Actors Theatre of Louisville, where I got my equity card, making me a member of the Actors’ Equity Association, and a true theatre professional,” she says.

Finding her footing in a brand-new career

After a few years of “adventuring,” Anderson moved back west and realized that she wanted a career—a legal career. Inspired by the 1970s television series “Petrocelli” she watched as a teenager, Anderson recalled Tony Petrocelli, a public defender living in Arizona who successfully represented clients wrongly accused by the system.

“I thought, ‘If I’m not going to be an actress, I might be able to do that,’” Anderson says.

She took the LSAT, applied to only one school, and received her admissions letter from Utah Law on Valentine’s Day in 1990.

“I had a huge naivete about the law. It was all just strange to me, and I didn’t think I understood any of it—I was an imposter.” Anderson says. “I had this grand idea of helping people, but I didn’t know what that meant or looked like or who these people were. I was absolutely convinced they were not going to be in the criminal justice system. It was the one area I didn’t want to have anything to do with.”

Anderson didn’t know then that her future did indeed lie within the criminal justice system. However, her advocacy work began during her first summer in law school, when upperclassman Kay Fox (’90) introduced her to outreach for those experiencing homelessness.

“I would go on Sunday mornings where they served breakfast to the homeless and set up a table with a sign that said ‘free legal advice.’ I would talk to anybody about any kind of legal problem they had,” Anderson recalls. “Sometimes students would come with me, sometimes other attorneys would come with me, and sometimes I was alone.”

Anderson continued this outreach for nearly three decades—until the COVID-19 pandemic hit. She worked a few different jobs after law school before finding her niche, beginning as a litigation associate at Holme, Roberts & Owen (1993–1994). She then worked at the American Civil Liberties Union as legal director from 1994–1997 and joined Cannon, Cleary & Match in 1997, specializing in social security law and indigent criminal defense.

Pioneering innocence and post-conviction work in Utah

In 1999, Anderson returned to Utah Law as a faculty member. Shortly after taking her new position, Professor Lionel Frankel asked Anderson to join him in developing a new innocence project. Together, they founded the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center. Much to her surprise, it was an area of law that deeply resonated with her.

“I didn’t know anything about innocence work, but I knew that I still wanted to help people. I got involved and found that it was exactly what I had always looked for,” she says. “The goal of innocence work at its most base level is to bring innocent people home from prison. But then you can look at the reasons why that person was in prison in the first place and potentially make systemic change.”

In fact, Anderson participated in policy work to change the law and establish new laws in Utah, Wyoming, and Nevada that would help innocent people return to court and address the causes of wrongful conviction.

For over 20 years, she ran the Innocence Clinic at the College of Law. She remarks how meaningful it was to teach and share this work with students over the years.

“Innocence cases take quite a long time, and you can’t get it done in a semester or two. So students would do the Innocence Clinic and get their cases to a certain point, but then they’d either graduate or move on,” Anderson says. “Very often when we were ready to start litigating the case, we could find that student in a firm and say, ‘Do you want to work on this pro bono?’ The student knew the case because they worked on it, so they could dive right back in and help with the final exoneration of that individual. It was incredible to see them go from being a student to being a lawyer and really making a difference in people’s lives.”

Anderson even recalls one student going to great lengths to see their client walk out of prison in 2011 after an eight-year case.

“One of the students, who worked with me on an innocence case from 2002-2005, started the case but then became a public defender in New Hampshire after he graduated,” Anderson says. “When we got that exoneration—when we brought Debra Brown home in 2011—he flew from New Hampshire so he could be there when she walked out of prison. So many students wanted to stay involved in the work, even if they were at a firm or doing something different. They wanted to continue advocating for the client they met in law school, and that was awesome!”

In 2022, Anderson expanded the innocence work to include post-conviction work and now runs the Post-Conviction Clinic, which allows students to help both innocent individuals and those whose constitutional rights were violated in other ways by the criminal justice system. She says innocence and post-conviction work has been both the most challenging and most rewarding of her career. Many times—even while doing the homeless outreach—she wondered if she was making a difference in people’s lives.

“These cases can be incredibly frustrating and hard. You hit hurdles at every turn. But there’s nothing like walking an innocent person out of prison and bringing them home to their families or helping them readjust to the community.” Anderson says. “At the same time, the reward was teaching students how to do innocence and post-conviction work and to feel passionate about it or to be passionate about helping individuals to access justice—whoever they are.”

Reflecting on 25 years at Utah Law

After teaching more than 25 years, Anderson says it’s the community that makes Utah Law so special.

“The students have been amazing from the first year I taught—their enthusiasm, passion and excitement. As a legal writing professor, I have mentored a lot of students because I have them for the full year. Most professors only have them for one semester. I do a lot of individual work, so I get to know the students in my class really well,” Anderson says.

Moreover, she appreciates that Utah Law has always been supportive of its students and faculty members exploring their legal interests.

“When I was in law school, I worked on an exciting class-action case against the Social Security Administration where I interviewed plaintiffs and helped figure out strategy. It was unique for a law student, and no one tried to stop me. They said, ‘Good for you. You’re getting this experience,’” Anderson says. “Then I came to teach here and developed the innocence work. I received so much support—to involve students in it and then turn it into a clinic. There has always been a lot of support to explore what’s important to you and to help students explore what’s important to them—to help them find their niche. I love that part of the job.”

Many people have influenced Anderson throughout her career to be a better lawyer or simply to be a better person. She feels a kinship to her fellow 1993 classmates and recalls rubbing shoulders as a student with former Associate Dean for Admissions and Financial Aid Reyes Aguilar (’92). Her greatest legal mentor was Lee Teitelbaum, Utah Law dean from 1990–1998, who shared some poignant lessons with her.

“Dean Teitelbaum was an incredible mentor to me. He taught me more about the law than anybody ever did just in the way he thought about it. He had a gentle nature and an incredible brilliance,” Anderson says. “He and I would stand outside the law school and smoke our cigarettes together (I quit 22 years ago). Dean Teitelbaum would just talk about the law—what he thought about the law and why he was in the law. I took every class I could possibly take from him.”

In addition, Anderson remembers her dad as her greatest champion. When she made the hard transition from the theater to the law, he was there to offer support.

“My dad was a professor of English and theatre at Utah State University and the smartest human being I’ve ever met—but also the most compassionate. He was so excited when I decided to go into the law. He encouraged me in everything that I did, no matter how down I was or how hard it was. He was supportive at every turn and gave me invaluable advice,” Anderson says.

Embarking on her final semester as a professor

This June, Anderson will retire from Utah Law. She follows the careers of the 600+ students she’s had over the years and continues to be their friend and mentor.

“It’s the students I’m going to miss the most when I retire. People joke with me because anywhere I go now, I can say ‘Well, that was my student and that was my student and that was my student.’ And I’m not going to be able to say that anymore. This is my last class of 1Ls this year, and it’s bittersweet,” Anderson says.

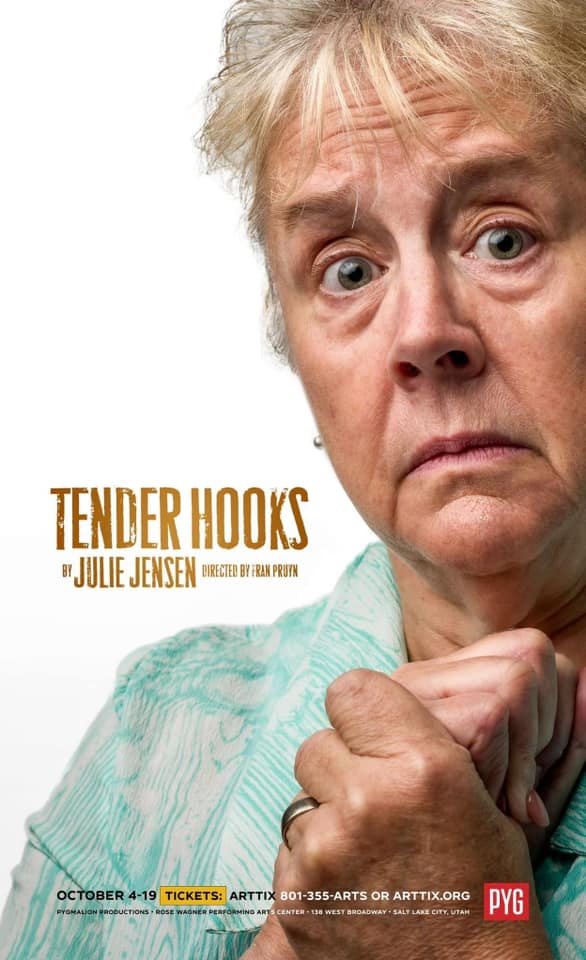

However, she looks forward to slowing down—to spend time with family, travel, “pick and choose” her legal projects, or perhaps explore more theatre work now that she has recently returned to the stage. Her possibilities are endless.

“People ask me if I’m excited. I just feel serene. It’s the right decision and the right time. I think infusing some new blood into the law school will be a good thing. I’ll never lack for things to do—they can be law-related or not. But slowing down seems like a good idea,” Anderson says. “It’s strange being one of the old ones here. When I started teaching, professors I had in law school were still here. It was odd to be their colleague and not their student. Now it’s the other way around. It’s been a great journey.”