This post by Jeff Ostermiller is reprinted with permissions from the Utah Department of Environmental Quality for EDRblog.org

Sometimes it’s hard for me to keep my inner cynic in check. This is particularly true during presidential elections, when the divisive nature of our political system makes compromise among differing viewpoints seem impossible.

In contrast to presidential politics, our collaboration on Willard Spur embraced divergent views to help find solutions to a seemingly intractable problem. We went from several legal challenges to unanimous consensus on appropriate resolution to several water quality issues — a journey that was only made possible by genuinely listening and responding to divergent stakeholder perspectives.

Challenges

The process started with a legal challenge to a discharge permit for a newly constructed wastewater treatment plant to Willard Spur, a non-tidal estuary of Great Salt Lake. Unlike other waters in the state, Great Salt Lake generally lacks numeric criteria, which are water quality pollution limits that are protective of the beneficial uses of waters. The lack of criteria necessitate careful evaluation of each challenge on a case-by-case basis, usually by several water quality scientists with different areas of expertise.

Our first step in evaluating this particular challenge was to compile all of the data we could find. A review of our water quality database revealed — nothing! There was not a single water quality record among the millions of records in our archives. This was our first sign that this challenge might be different.

Meanwhile, the legal and political contentions expanded to include the Bear River National Wildlife Refuge. The Water Quality Board was also petitioned to increase the regulatory protections for Willard Spur by making changes to Utah’s water quality standards.

Perry and Willard Cities, the proud owners of a new $20 million treatment plant, were understandably concerned about not being able to operate. Our preliminary analyses were unable to conclude with a reasonable amount of certainty that it was unlikely that the facility on Willard Spur caused impacts to the Spur. However, given the lack of data, any conclusions were, at best, tenuous.

Only one fact was clear: Willard Spur is an important—and stunningly beautiful— ecosystem warranting protection.

Collaboration

We were able to establish a process that allowed the facility to operate on a temporary basis while DEQ and others collected the data necessary to make defensible long-term permitting decisions. A Steering Committee of representatives from all parties directly affected by the project was formed to guide the project and making recommendations to the Water Quality Board on permit requirements or water quality standard changes. A Science Panel was also formed with experts in a variety of important disciplines. This team identified important data gaps and made recommendations about investigations most critical to resolving stakeholder concerns. My role was to lead this panel.

We were able to establish a process that allowed the facility to operate on a temporary basis while DEQ and others collected the data necessary to make defensible long-term permitting decisions. A Steering Committee of representatives from all parties directly affected by the project was formed to guide the project and making recommendations to the Water Quality Board on permit requirements or water quality standard changes. A Science Panel was also formed with experts in a variety of important disciplines. This team identified important data gaps and made recommendations about investigations most critical to resolving stakeholder concerns. My role was to lead this panel.

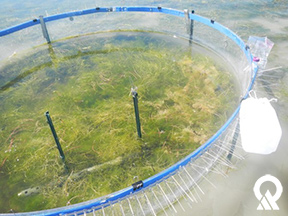

Over the next several years, we conducted numerous research projects. Everyone was actively engaged throughout all steps of the project — from planning through implementation and ultimately interpretation of data — always in the context of divergent stakeholder concerns.

Solutions

Ultimately, we learned enough about the ecosystem to make recommendations for permit renewal that minimized the risk of the discharge to the health of the ecosystem. As it turned out, they also resulted in reduced operating costs for the facility! These recommendations received unanimous support from Steering Committee members, consensus that few would have guessed possible at the beginning of the project.

While it is true that we got lucky in the sense that scientific investigations don’t always lead to equitable solutions, I’m convinced that the collaborative nature of the project increased the likelihood of finding a sensible solution that was acceptable to all stakeholders. In part, this is because consideration of different goals and perspectives was central to the study design. Over time, this open dialogue also built trust among stakeholders, which I believe would have made more contentious resolutions more palatable if the data suggested they were necessary.

Final Thoughts

On a personal level, it was gratifying to work with a diverse group of stakeholders and scientists. It was impressive to see work of the Science Panel and Steering Committee, all of whom demonstrated their commitment by volunteering many hours of their time to provide thoughtful advice. Our monitoring section and outside contractors work tirelessly to collect the information requested. I’m extremely grateful to everyone involved.

Sometimes we all get frustrated with the amount of time required for meaningful change in the public sector. For me, this project served a reminder that sometimes delays result from the legitimate need to truly understand the perspective of those who might be affected by our policies and to collect sufficient information to make sure that whatever decisions are ultimately made are as informed as possible.

Want to learn more about the Willard Spur collaborative process? Visit our websitefor more information. Better yet, visit the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge and experience this beautiful place for yourself!

Jeff Ostermiller is an environmental scientist for the DWQ who has had many roles since I joined the team 12 years ago. Currently, I’m overseeing efforts to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, an important, largely unaddressed water-quality concern. When not working at DEQ (or at home), I enjoy taking adventures with my family. Whether we’re on local outdoor excursions or on travels to new and interesting destinations, my pleasure is enhanced by the naturally inquisitive, youthful exuberance of my son and daughter.

Jeff Ostermiller is an environmental scientist for the DWQ who has had many roles since I joined the team 12 years ago. Currently, I’m overseeing efforts to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, an important, largely unaddressed water-quality concern. When not working at DEQ (or at home), I enjoy taking adventures with my family. Whether we’re on local outdoor excursions or on travels to new and interesting destinations, my pleasure is enhanced by the naturally inquisitive, youthful exuberance of my son and daughter.