By Professor James R. Holbrook

Psychologists Joe Luft and Harry Ingham were researching human personality at the University of California-Berkeley in the 1950s when they devised their “Johari Window” named after a combination of their two first names. The Johari Window is a way of looking at how personality traits are expressed and concealed. Luft and Ingham observed:

- there are aspects of our personality of which we are aware;

- there are aspects of our personality that others see in us of which we are not aware;

- there are aspects that we know about ourselves that we keep hidden from others; and

- there are aspects of our personality that are unknown to anyone, including ourselves.

This model is used to increase self-awareness and improve communication among individuals in a group.

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

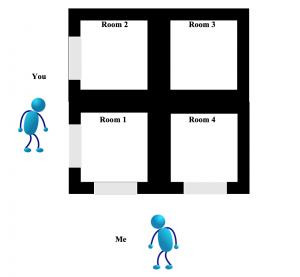

For our purposes as negotiators and facilitators, the four Johari Rooms illustrate four categories of our knowledge about the world and its limits in terms of what we and others can and cannot “see” in the different rooms:

- You and I can both see into Room 1. Presumably, we see the “same things” in Room 1, but we know from experience that we each sometimes see something different when we are looking at the “same thing.” For example, although we are both looking at a photograph of children in a fenced-in room at a facility on the U.S. southern border, I see undocumented aliens who crossed the border illegally, whereas you see vulnerable children suffering irreparable adverse childhood experiences. We simply don’t see the same thing in that photograph.

- You can see into Room 2, but I cannot. So, there are things you know that I do not know. Some of what you know may be important to me but unknown by me—that could be a problem for me.

- Neither of us can see into Room 3. This is the room that contains what Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously called the “unknown unknowns”—things we don’t know we don’t know. For example, before the invention of the personal computer, typewriter manufacturers could not know the future disruptive technology that would destroy their industry.

- I can see into Room 4, but you cannot. So, there are things I know about me that you do not know. Some of what I know may be important to you but unknown by you—that could be a problem for you.

The illustration about the Johari Rooms also implicates six counterintuitive character traits and related behaviors that are very useful to us in effective negotiation, mediation, facilitation, and conflict communication:

- Empathy – I must try to understand what you know from your perspective, including your perceptions, assumptions, and values that differ from mine.

- Humility – I must recognize the limits of what I know, including my limited perceptions, assumptions, biases, prejudices, and the possibility I am wrong about what I believe I know.

- Courage – Because you may know more than I know, I must ask you to tell me what you know, and it is scary for me to reveal to you the limitations in what I know.

- Trustworthiness – I must incentivize you to tell me what you know by treating you with civility, courtesy, and respect, and by carefully paying attention and listening to you.

- Curiosity – I must listen to what you say, understanding that you may “spin” what you disclose or you may choose not to tell me something specific.

- Open-mindedness – If you tell me something important that I did not know, I must be willing to be affected by your perspective, feelings, or interests.

The Johari Rooms are a powerful conceptual tool for us to use in negotiation, mediation, facilitation, and conflict communication. It operationalizes empathy into specific strategies and behaviors. It enables us to learn the perspectives and emotions of others. It helps us overcome “advocate’s bias” and the mistaken belief that we already know everything we need to know. It incentivizes us to be trustworthy in our dealings with others and to disclose our perspective and emotions to others. It enables us to obtain useful information we did not know, on the basis of which we may be willing to change our position or our demands. It enables us be more creative and comprehensive in generating options and in increasing value that better satisfies our important interests and the important interests of others. In short, it helps us to be more collaborative and effective.

James Holbrook graduated from the University of Utah College of Law in 1974 and practiced law in Salt Lake City for 28 years as a trial lawyer before joining the faculty at the S.J. Quinney College of Law in 2002 as a Clinical Professor of Law teaching negotiation, mediation, and arbitration. He has mediated and arbitrated over 1,000 disputes dealing with a wide range of legal issues.