By Steven C. Beda for EDRBlog.org

Harney County, Oregon is broad, flat, and expansive. Were the title not already claimed by Montana, this place could be properly called big sky country.

Harney County, Oregon is broad, flat, and expansive. Were the title not already claimed by Montana, this place could be properly called big sky country.

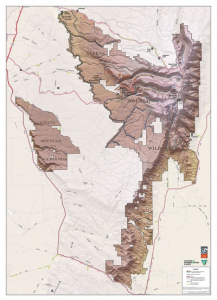

The one exception to Harney County’s flat landscape is the Steens Mountains: a hulking formation of basalt and rhyolite lava flows left over from the last volcanic eruption 8 million years ago. The slopes of the Steens gradually rise up from Harney County’s grassland plains to more than 9,000 feet before plummeting into the Alvord Desert.

The physical presence of the Steens is matched only by the intensity of land-use conflicts that have taken place on its slopes: first between Native Americans and the US Government; then between Basque sheep herders and cattle barons; and finally among the environmentalists, ranchers, and the Bureau of Land Management.

But in 1999, something happened that quieted conflict on the Steens: ranchers, environmentalists, the BLM, and the Burns-Paiute Tribe reached an unprecedented land-use agreement that has since transformed Harney County into a model of collaborative resource management.

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

This may come as something of a surprise for those who only know Harney County as the place where anti-government protesters occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in early-2016. The reality is that those occupiers weren’t from Harney County and certainly didn’t speak for the people of Harney County. When asked, most ranchers here will tell you that they’re extremely proud of their ability to sit down with their former political adversaries and work out their differences in ways that don’t involve rifles and threats. The story of how Harney County got here begins with that 1999 agreement reached on the windswept slopes of the Steens.

I’m a historian who studies the rural Pacific Northwest. Most of my research has been about the timber industry, where conflicts today are almost as vitriolic as they were thirty years ago when radical environmentalists drove spikes through trees and loggers hung dead Spotted Owls from signposts.

I’m a historian who studies the rural Pacific Northwest. Most of my research has been about the timber industry, where conflicts today are almost as vitriolic as they were thirty years ago when radical environmentalists drove spikes through trees and loggers hung dead Spotted Owls from signposts.

We historians are trained to look for contingency, for those moments when a different choice or action might have set history down a different course. But study Northwest timber country long enough and you start to lose sight of contingency. Forest debates have often been so fierce and so long lasting that it’s easy to forget that things might have gone another way.

That’s why I’m drawn to the history of the Steens. It shows that another path was, and is possible.

But it almost didn’t happen. Like many things in history, Harney County was set down this path somewhat by a chance event.

In August of 1999, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbit was sitting in a plane with then-Oregon governor John Kitzhaber, 30,000 feet over eastern Oregon. Babbitt just happened to look out the plane’s window as it crossed the Steens, and what he saw awed him.

“I was impressed with the whole area,” he later told Stephen Stuebner of High Country News. “It’s the only place I’ve seen where you have alpine glacial valleys end in the desert.”

A few days later, Babbit officially announced that he was going to seek a National Monument designation for the Steens, and in so doing waded into the middle of decades of conflict.

Ranchers had been running cattle on the rich grassland slopes of the Steens since the nineteenth century without much opposition. But in the 1960s environmentalists started to argue that grazing threatened the Steens’ delicate ecology.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, environmentalists pursued wilderness designations on the Steens but always failed, largely because of counter-pressure applied by Harney County residents who feared that federal protections would threaten their ability to graze cattle on the Steens’ BLM lands.

The conflict never erupted into a full out sagebrush rebellion, as similar conflicts throughout the West had, but tensions were certainly high and it looked as if a modern range war was looming.

Now here came an Interior Secretary with a recent record of National Park expansion, working for Bill Clinton, a president looking to curry political favor with environmentalists, and the country was heading into an election year, no less.

If the first chance event in this story is Babbit’s flight over the Steens, then the second is Oregon Congressman Greg Walden’s decision to intervene in early-2000. Equally sympathetic to people on all sides and hoping to avoid a conflict, Walden convinced Babbitt to hold off on the monument designation, then convened a panel of ranchers, environmentalists, and representatives of the Burns-Paiute Tribe to attempt to work out a solution.

Babbit’s willingness to delay the National Monument designation was only temporary, which meant the clock was ticking for Walden’s group as they met over the course of three days at the Roaring Springs Ranch at the base of the Steens.

We have no formal record of what took place there, and that’s a shame, because whatever conversations happened were entirely unprecedented in Harney County’s history, if not the history of the American West. For decades, environmentalists, ranchers, and tribal members had pursued all-or-nothing approaches. Either cattle could range across the entire mountain or the whole of the Steens needed to be preserved or protected.

Yet, when the group emerged, they had arrived at a settlement in which each side gave a little. The final agreement proposed a 105,000 acre “cow-free wilderness” in the more delicate, high-elevation portions of the mountain and would allow continued grazing in the lower-elevation grasslands.

Walden shepherded the proposal through Congress and then it was signed into law by Clinton as the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Act of 2000.

Had the act ended with land-use designations, it would still be important. But the act did something else that truly revolutionized land-use politics in Harney County: it permanently established a twelve member committee composed of ranchers, environmentalists, Burns Paiute Tribal Members, and hunters called the Steens Mountain Advisory Committee (SMAC) and further required the BLM to consult with the panel before implementing any management decisions.

It would be easy to take a cynical view of SMAC’s creation and say that the looming threat of the National Monument forced people into a collaborative partnership, and that might be true. But it’s equally true that SMAC changed the tenor of land-use discussions in Harney County. By forcing conversations between former adversaries, the panel encouraged environmentalists, ranchers, and tribal members to see each other less as existential threats and more as people with whom they simply disagreed.

As people learned to talk with one another rather than over one another as they’d done for much of the past, Harney County became a far more amicable place. Since the creation of SMAC three decades ago, dozens of additional collaborative partnerships have emerged here with people regularly meeting to collectively develop management plans for everything, from water allocation to fire management. Today, Harney County is perhaps the most collaboration-oriented place in the entire American West.

The lessons to be drawn from the Steens Mountians, then, are that the land-use conflicts that have defined much of the American West’s history are not destined to continue into the future. Other paths are possible. That’s a lesson that would serve not just Westerners but Americans more broadly.

Steven C. Beda is an assistant professor of history at the University of Oregon. His research explores the way rural communities in the Northwest have used, managed, and fought over nature. He’s currently at work on a book about the history of Northwest timber workers. He teaches classes on environmental history, Pacific Northwest history, and 20th century US history. He can be reached at: sbeda@uoregon.edu.

Steven C. Beda is an assistant professor of history at the University of Oregon. His research explores the way rural communities in the Northwest have used, managed, and fought over nature. He’s currently at work on a book about the history of Northwest timber workers. He teaches classes on environmental history, Pacific Northwest history, and 20th century US history. He can be reached at: sbeda@uoregon.edu.