By Eric Balken for the EDRblog

News coverage of drought has become inescapable for those of us living in the west. Talk of prolonged water shortage has been top of mind for years, but reached a tipping point this year with Lakes Powell and Mead dropping to their lowest levels since they began filling. The very foundation of Colorado River policy is facing a reckoning; one presaged by an over-allocation of water and now supercharged by climate change.

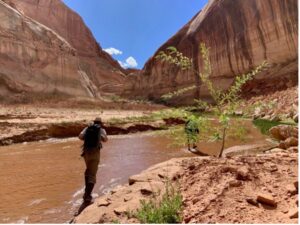

Meanwhile in Glen Canyon, a kind of miracle is happening in front of our eyes. The canyon whose loss was considered to be our country’s greatest environmental mistake is coming back to life. A silver lining amidst the dower realities of our mismanagement of water, the canyon thought to be lost forever is being reborn and offers new opportunities for management and collaboration.

Before Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1963, it was considered heaven on earth to those who knew it. It was revered by western writers, such as Wallace Stegner, who said, “it would make a superb national park.” It attracted photographic luminaries like Elliot Porter, Philip Hyde, and Tad Nichols. John Wesley Powell, the civil war vet whose exploration and documentation of the river turned the world on to its wonders, wrote in his book Down the Colorado, “we have a curious ensemble of wonderful features—carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcove gulches, mounds, and monuments—we decide to call it Glen Canyon.”

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

Importantly, the canyon is a significant place to many Native American tribes: Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Paiute, and Pueblo. Several tribes called it home at the time the dam was commissioned, with some members being displaced and losing farms, orchards, grazing land, and sacred sites to the reservoir. The losses incurred by tribes weren’t widely covered, but there are some accounts of what they experienced.

In the years after Glen Canyon dam was completed, it inundated 186 miles of the Colorado River, as well as the lower reaches of the San Juan, Escalante, and Dirty Devil Rivers, effectively destroying a massive habitat for plants and wildlife in the heart of the Colorado Plateau. It completely changed the ecosystem downstream in the Grand Canyon, starving the river of its warm silty water and replacing it with cold, clear water.

These impacts stirred a new wave of environmentalism in the U.S., with groups like the Sierra Club becoming a powerful voice and stopping proposed dams in the Grand Canyon. The “reclaiming” of Glen Canyon was a far-fetched dream of environmentalists, and for decades seemed well outside the realm of reality.

Then in 1996, Glen Canyon Institute (GCI) formed with the help of former Sierra Club director David Brower to see how far-fetched the dream really was. The goal of GCI was to restore Glen Canyon, and the first step was to bring together groups of different stakeholders with mutual interests to explore the idea. By bringing together scientists, academics, artists, activists, and even folks who worked for the Bureau of Reclamation, GCI established areas of mutual concern, and led to our first major study, the Citizens Environmental Assessment.

The collaboration in the early days wasn’t clean or easy, but it helped GCI focus its work in areas that could be most effective. GCI’s first event was a debate between David Brower and former commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, Floyd Dominy. Behind the scenes Brower and Dominy had a tumultuous, yet compassionate relationship. Their conversations would shift between screaming at one another, then hugging and crying on each other’s shoulder. GCI stayed engaged with Dominy, who eventually explained to us the engineering required to phase out Lake Powell.

The early dialogues also helped flesh out differing views from environmentalists, like those that held a firm position that the dam should be torn down, or those who thought it should be decommissioned. Some academics suggested a more worthy cause would be fighting to restore Flaming Gorge upstream. Ultimately, these conversations led us to the policy proposal of “Fill Mead First”, operating Glen Canyon as a backup facility after prioritizing water storage in Lake Mead. This approach, with the aim of being as practical as possible, helped move the Glen Canyon restoration movement from the fringe into the mainstream.

In more recent years, the reservoir behind Glen Canyon dam has been hovering around half full, and right now it sits at 30% of capacity. Climate projections suggest it will never fill again, and could dip below the level at which it produces hydropower by 2023. These realities are hastening the renegotiation of the river’s management, set to be re-written by 2026.

All the while, Glen Canyon is transforming in real time. Iconic landmarks like Cathedral in the Desert have come out of water, with sediment being rapidly cleared by flash floods. Gregory Natural Bridge, one of the largest bridges in the country, is revealing the top of its span for the first time since 1969. Waterfalls, arches, amphitheaters, trickling streams and the riparian habitats they support are coming back to life. Cottonwoods and willows are establishing themselves once again, as bugs, birds, frogs, and lizards reinhabit the canyon.

Once seen as a temporary fluke, the reemergence of Glen Canyon is now gaining attention from national press, begging the question of how the canyon should be managed and what the value of its emerging resources are. Much of GCI’s work in recent years has been to highlight the value of these resources, both qualitatively through photos and writing and quantitatively through ecological research. To do this, we’ve used a collaborative approach, working with other entities like the Park Service and USGS, as well as other conservation and research organizations who have a mutual interest in Glen Canyon’s emerging resources.

As the transformation of Glen Canyon continues, it’s imperative the approaches to its management remain collaborative. When the dam was commissioned in 1956, the interests of the tribes, conservationists, and the needs of the ecosystem were not taken into account. However, in the new Glen Canyon, incorporating these interests will ensure we make the most of this incredible opportunity.

Eric is the executive director of Glen Canyon Institute. He has been involved with Colorado River policy for the past decade, helping spearhead multiple research and advocacy initiatives at GCI. Eric has a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies and Geography from the University of Utah and serves as an advisor on the Future of the Colorado Group.

Eric is the executive director of Glen Canyon Institute. He has been involved with Colorado River policy for the past decade, helping spearhead multiple research and advocacy initiatives at GCI. Eric has a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies and Geography from the University of Utah and serves as an advisor on the Future of the Colorado Group.