Most aspects of life in the early 21st century go beyond easy analysis and resolution. The subject of ranching, particularly in the context of wildlife conservation in the American West, is bound then to aggravate anyone who demands singular causes and fixed solutions. The stories of ranchers have been told in countless forms over the years, yet rarely have they actually been told by ranchers themselves.

Most aspects of life in the early 21st century go beyond easy analysis and resolution. The subject of ranching, particularly in the context of wildlife conservation in the American West, is bound then to aggravate anyone who demands singular causes and fixed solutions. The stories of ranchers have been told in countless forms over the years, yet rarely have they actually been told by ranchers themselves.

Recognizing a gap in the ethnographic literature and a need for nuance in our approaches to human-wildlife coexistence, I spent a decade amongst the ranching communities of western Montana and wrote a book about producers and their partner organizations who are forging new paths in conservation to sustain working ranch operations alongside healthy wildlife populations. The Atlas of Conflict Reduction: A Montana Field-Guide to Sharing Ranching Landscapes with Wildlife (Anthem Press, 2022) is a compilation of first-hand stories of ranchers that takes readers on a journey up the western slope of Montana and ties in psychological concepts to illustrate a new paradigm for overcoming deeply divisive conservation challenges.

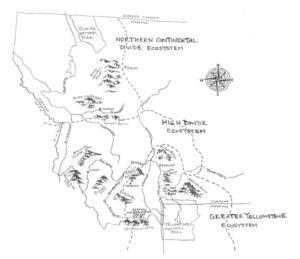

To begin, chapter one outlines the social and environmental history of western Montana. Western Montana’s landscape and its inhabitants reflect a long and conflict-laden history of social meaning and environmental decision-making regarding the flora, fauna, and people who call it home.

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog. Sign up for our email list »

Chapter two then illustrates how the economy and way of life for ranchers in western Montana is embedded in a much larger story about the places people hold dear. I explain the concepts of place identity and place attachment by traveling along with the Martinell family and other local ranchers on their daily acts of living, working, and playing in the Centennial Valley. By illustrating these concepts, readers can begin to identify commonalities with ranchers, particularly a shared desire to protect valued “places” like the Centennial Valley.[i]

As readers learn about in chapter one, a suite of conflict-prevention tools exist to manage the physical, ecological, and economic threats livestock-wildlife conflicts can present. However, what is often missing from accounts about these tools are the contextual factors shaping people’s willingness to use them. Chapter three integrates research on the psychology of decision-making with success stories from the Big Hole Watershed Committee (BHWC) and local ranchers from the Big Hole Valley to help readers understand the critical components essential for implementing any type of effective and collaborative conservation strategy.

I take readers to the Ruby Valley in chapter four and uncover what I call the “culture of nature” surrounding humankind’s relationship to the environment. The idea we need to “get back to nature” has long been echoed in various media outlets and conservation publications.[ii] What is absent from these accounts is a harsh reality: there is no such thing as a “pristine” nature we can get back to at this point. By interacting with the natural world, we inherently alter it. Through discussions with family members from the Helle Ranch and its affiliated clothing brand, Duckworth, we learn about efforts to keep the ranch in the family through the creation of value-added enterprises, while also stewarding the land and wildlife.

Chapter five explores the historical and contemporary myths and mythologies surrounding wildlife and livestock. Through an introduction to the ways that animals are ‘beasts of burden,’[iii] I uncover the underlying reasons for people’s divisive reactions to them. I include stories from Becky Weed, a Predator Friendly® Certified Rancher in the Gallatin Valley, who describes her decision to be a part of this label and why being classified as ‘predator-friendly’ is so controversial.

In chapter six, we head into the Tom Miner Basin of Paradise Valley, where I share the thoughtful efforts the Anderson family is undertaking to uphold a more holistic, regenerative approach to ranching and managing their landscape for the betterment of everyone. This chapter introduces readers to groundbreaking research on the science of soil health and regenerative agriculture. Reiterating the idea that we cannot afford to lose the family ranch, the story of the Anderson family helps readers see the unparalleled opportunities existing when we support them.

Finally, chapter seven ties these ideas all together and concludes the book by capturing the stories of the ranchers, agency scientists, and NGO staff who are a part of the Blackfoot Challenge. For anyone attempting to study how to achieve a successful collaborative conservation effort, it will not take them very long before they come upon the Challenge in their research. As stories from local ranchers attest, it is the challenge’s commitment to building trust, proper pacing, and nourishing relationships that is at the heart of this organization’s decades-long endurance and ability to realize a shared vision for how they want their special place to endure into the future.

There is, sadly, no universal panacea to solve the types of modern conservation problems we face, but there are ways we can better address them. This book is a roadmap for how anyone concerned about the fate of our lands and their inhabitants can begin to do so.

[i] Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

[ii] Wilson, A. (1991). The culture of nature: North American landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez. Toronto: Between the lines.

[iii] Credit goes to the Rolling Stones for their classic song title, but the ideas behind my usage of the term has more to do with these publications: Clark, T. W., & Casey, D. (1992). Tales of the grizzly. Moose: Homestead Publishing. And: Clark, T. W., & Casey, D. (1995). Tales of the wolf: Fifty-one stories of wolf encounters in the wild. Moose: Homestead Publishing

Hannah Jaicks, PhD, is an interdisciplinary scientist working with rural communities on how to coexist with native wildlife to improve the stability of wild and working landscapes for human and nonhuman animals and the author of The Atlas of Conflict Reduction: A Montana Field-Guide to Sharing Ranching Landscapes with Wildlife. She is currently the Working Lands Initiative Program Director for Future West based out of Sheridan, Montana. When she’s not at work, she’s winding up locally sourced, wildlife friendly wool for her latest knitting project to improve local textile supply chains.

Hannah Jaicks, PhD, is an interdisciplinary scientist working with rural communities on how to coexist with native wildlife to improve the stability of wild and working landscapes for human and nonhuman animals and the author of The Atlas of Conflict Reduction: A Montana Field-Guide to Sharing Ranching Landscapes with Wildlife. She is currently the Working Lands Initiative Program Director for Future West based out of Sheridan, Montana. When she’s not at work, she’s winding up locally sourced, wildlife friendly wool for her latest knitting project to improve local textile supply chains.