By Sarah Daitch & Jordi Honey-Rosés

Poor preparation and facilitation can lead to participants feeling underappreciated, not listened to or frustrated. The way dialogues are designed and facilitated, in particular for decision making on issues of public concern, can make an immense difference when it comes to meaningfully engaging citizens and fostering collaboration. However, the question of what type of structure is most effective for these sessions has rarely been tested in a formal experiment.

This is relevant for businesses, large organizations and local city governments. In collaboration with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the Canadian International Resources Development Institute (CIRDI), and the University of British Columbia, we compared two common facilitation approaches during a UNDP workshop: a highly structured multi party dialogue, and an unstructured multi party dialogue. Our findings were published recently in the Journal Group Decision and Negotiation

At a UNDP convened workshop on Participatory Environmental Governance for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Latin America, which took place in Panama City in late 2018, 40 participants gathered to discuss participatory environmental monitoring committees associated with mining. The participants included members of community monitoring committees from Argentina, Bolivia, Panama and Peru, as well as subject matter experts, NGOs and representatives from donor agencies.

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

In our experiment, workshop participants were split into two comparable groups for one session, to understand how the use of structured or unstructured facilitation approaches might change participant satisfaction and equity in participation. Participants were asked to identify challenges associated with the establishment and operations of participatory environmental monitoring committees in the mining sector. After an ideas generation phase, they were asked to prioritize the challenges faced by committees, and select the two most important challenges, which would be the focus for the rest of the two day workshop. In our experiment, structure consisted of three differences between the groups – first, a more directed facilitation approach, second, dividing the participants within the group into small groups to complete some of the work, and third, the facilitator imposing a specific prioritization method for the group to jointly select the most important challenges.

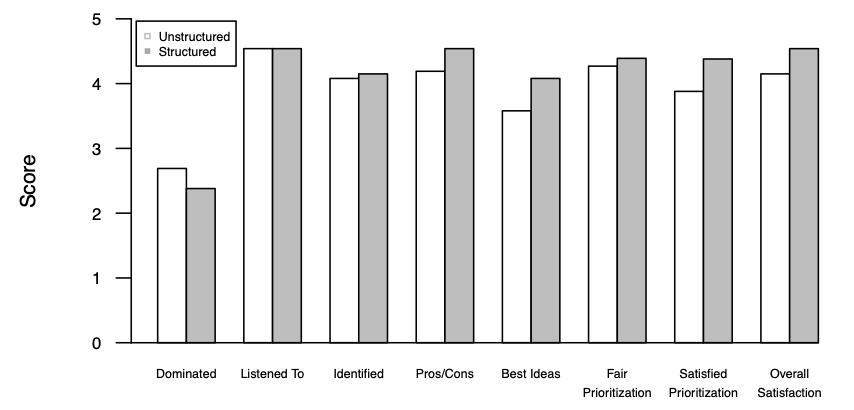

In the structured session, participants felt that as a group, they did a better job weighing the pros and cons of different ideas; they were more confident that the best ideas were selected; and they were satisfied with the prioritization process and the session overall, and were less likely to say that a few people dominated the session.

Figure 1. A comparison of participant responses in unstructured sessions (white) and structured sessions (gray).

The findings showed that structured facilitation with small group discussions provided a small yet consistent improvement over the less structured approaches. Participants were more satisfied with the structured sessions because they felt that the best ideas were listened to. We found men and women have different perceptions about the level of women’s participation. Male participants were more likely than women to report a high degree of participation of women, whereas women perceived that females spoke less than the men. This gender gap persisted in both the structured and unstructured dialogue groups. This is important to note, because women are frequently underrepresented in public dialogues or decision-making processes. If participatory dialogue processes are to address a range of public concerns in a fair manner, care must be taken to include women from a range of socio-economic and cultural groups. The design of the process must create space for these participants and their important and too often excluded perspectives.

We found that structure for the dialogue is especially valuable when the stakeholder group is diverse, the issues at hand are complex, and there are a range of different interests and possible outcomes. We observed that under certain conditions, there might be a measureable disadvantage to not providing group guidance on decision making, and that a decision-making method that is offered by a third party neutral may be more likely to be viewed as fair and impartial. When it comes to decision-making processes on complex issues, it is good facilitation practice to decide jointly on the decision-making criteria and methods early on, especially in conflict sensitive settings.

This is the first known study to compare different approaches for multi party dialogue facilitation with a formal field experiment. Research on meeting design and consensus building amongst multiple parties or organizations is composed mainly of case studies and other qualitative research. This research breaks from the existing body of work, and illustrates that experimental research designs are a feasible tool for learning about facilitation methods, and testing good practices in public participation and public sector collaborative process. Looking ahead, the ultimate aim of this work is to build a stronger evidence-base about how multi party dialogue events for decision making on complex public issues should be structured, in order to achieve better decision making, constructive outcomes and satisfaction amongst the parties.

Sarah Daitch is a mediator, dialogue process designer, and facilitator at Daitch & Associates, www.daitchassociates.ca – specializing in public dispute resolution and multi party collaboration on social, environmental, and sustainable development issues. Sarah provides services to governments, tribal governments, non-profits and companies in Canada, the US and Europe, and has supported dispute resolution and conflict prevention initiatives in in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Sarah is a Chartered mediator with the Alternative Dispute Resolution Institute of Canada; she also serves as a mediator with the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada. Sarah has worked extensively on conflict prevention associated with natural resources, with the United Nations Development Programme.

Sarah Daitch is a mediator, dialogue process designer, and facilitator at Daitch & Associates, www.daitchassociates.ca – specializing in public dispute resolution and multi party collaboration on social, environmental, and sustainable development issues. Sarah provides services to governments, tribal governments, non-profits and companies in Canada, the US and Europe, and has supported dispute resolution and conflict prevention initiatives in in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Sarah is a Chartered mediator with the Alternative Dispute Resolution Institute of Canada; she also serves as a mediator with the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada. Sarah has worked extensively on conflict prevention associated with natural resources, with the United Nations Development Programme.

Jordi Honey-Rosés is an Associate Professor in the School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. His research interests are in environmental planning and experimental methods.

Jordi Honey-Rosés is an Associate Professor in the School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. His research interests are in environmental planning and experimental methods.