By Danya Rumore

“It is the ability to choose which makes us human.” -Madeleine L’Engle

It is not often that I find myself reflecting on a book pretty much every day—and mentioning it to friends and colleagues almost as often. However, in a time when people generally seem to be stretched a little too thin, balls seem to get dropped a little too often, and I frequently feel like I am running around like a headless chicken, it is perhaps not surprising that Greg McKeown’s book Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less seems particularly relevant.

The ideas in the book are in many ways simple and nothing new. What is valuable about Essentialism is that it explicitly names and claims our tendency to engage in what McKeown refers to as an “undisciplined pursuit of more” and challenges us to think about how this affects not only ourselves, but also each other and society. Since reading the book, I have been doing a lot of thinking about this, particularly regarding how our well-meaning desire to “do it all” and to “say yes” creates unnecessary stress and internal and external conflict. As a result, I’ve become a proponent of the mantra “less but better” and am now making it part of my personal and professional manifesto.

The basic ideas of Essentialism is that, try as we might, we cannot have it all or do it all. Despite knowing that, we often act as if that’s not the case. We tend to assume “it is all important, “I have to do it,” and/or “I can do both X and Y and do them well.”

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

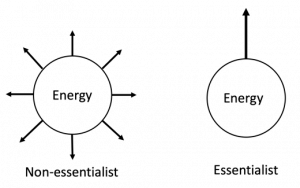

The result of this is that our limited energy gets scattered in every direction, instead of being focused and directed at the few things that really matter (the below drawing, which is modelled off of one that McKeown uses in the book, illustrates this difference). That, in turn, leads to people being spread too thin, balls getting dropped, feelings of being a headless chicken running around, and things generally not getting done or done well—all of which, in turn, often lead to unnecessary discontent, conflict, and potentially even disputes.

I think, for example, of research teams I am part of where everyone is excited about the research questions and project, but getting things done is like pulling teeth due to everyone (myself included) having too many other projects and commitments yanking at their attention. As a result, everyone gets frustrated (with themselves and/or with each other), deadlines get missed, and other projects also suffer due to this being one more thing everyone is trying to work on. If it gets bad enough, people don’t want to work together again, and potentially fruitful research partnerships are destroyed simply because people are overcommitted.

I also think of collaboratives I work with and facilitate. Participants want to get all sorts of things done—and arguable lots of things need doing—but in tackling one too many projects, nothing gets done, or things get done poorly. If this persists, the collaborative effort can fall apart, despite people’s commitment to work together.

To move beyond the undisciplined pursuit of more, McKeown advocates for “Essentialism,” or the “disciplined pursuit of less.” He argues (and I have to agree with him, based on my personal experience) that very few things we do or opportunities we pursue are essential or exceptionally valuable. Instead, a lot (and maybe most) of the things we put energy, time, and money into are “noise”; they are non-essential things that spread our focus and resources. Much the same, he notes that there are many good opportunities in life, but few great ones. He encourages us to acknowledge this, and to discern the “trivial many” from the “vital few.”

A core part of the Essentialism, he suggests, is accepting that there are always tradeoffs. Sure, you can do X and Y, but probably not do them both well, and whatever energy and time you are putting into Y is not being put into X. Instead of ignoring these unavoidable tradeoffs, we typically do better by being much more intentional about only spending our energy and time focusing on great opportunities, on the essentials. Instead of doing more and not doing it well, do less but better—and go big on a few really valuable opportunities.

To help put that into action, McKeown suggests we pause before committing to anything and ask ourselves questions such as:

- Is this essential?

- Is this a great opportunity (as in a top 10% opportunity) or just a good one?

- What are the tradeoffs of doing this and is this the best use of my limited time and energy?

- Does this fit the criteria of an excellent project or commitment? (Note, being able to answer this question requires we put some forethought as an individual or a group into what the criteria of an excellent project or commitment are.)

I find it is also helpful to ask the question: “Does this inspire and energize me?” If the answer is no and if there is no other reason the opportunity or thing is essential, I promise myself to say no. This question can also be helpful to groups—is the group inspired and energized by the opportunity or project, and is there someone who is passionate about moving it forward? If not, ask whether it is truly essential, and if it isn’t, maybe now is not the right time or it’s not a “great” project.

One of the benefits of practicing Essentialism is that, by not overcommitting, we leave buffers in our lives, which allows us to better deal with change and the unexpected. According to McKeown, Non-essentialists tend to overcommit, not leave buffer time, and generally underestimate how long something will take or how difficult it will be. “The way of the Essentialist is different,” he says. “The Essentialist looks ahead. She plans. She prepares for different contingencies. She expects the unexpected. She creates a buffer to prepare for the unforeseen, thus giving herself some wiggle room for when things come up, as they inevitably do.” (p. 179) Only focusing on the essentials means that, rather than having to miss an important deadline or cancel on a commitment due to an unexpected change, which often creates conflict, we have more space in our lives to effectively adapt and respond, and to jump on the great opportunities when they emerge.

Essentialism extends even to simple things like emails, words, and images. If we believe we can make things better by subtracting, not adding, we must ask ourselves: Is this email really essential? Can I say what I need to say in fewer words? Can I find one image that captures what I am trying to convey, rather than needing many images? Doing less but better takes some time though, but it usually is a good investment for yourself and for others. Think about, for example, if someone had just called you to ask you a really well-thought thorough question rather than sending a vague email which led to multiple emails back and forth and distracted you throughout the day. Our “undisciplined pursuit of more” and our failure to think about how we can do less but better not only takes a toll on us, it feeds an ongoing societal frenzy of Non-essentialism.

In an effort to practice what I now preach, I have committed to applying Essentialism to the Environmental Dispute Resolution Program’s efforts. We don’t do things to stay relevant; we do things that make us relevant. Before our program takes on a new project or commits to an event, we now ask ourselves: Is this a great opportunity? We have established clear criteria that we use to decide which projects to take on. And I make myself and encourage my staff to build in buffers for our time and energy so we can effectively respond to unanticipated challenges, which are an inherent part of conflict resolution work, and so we can seize those few great opportunities when they arise. My hope is that through embodying Essentialism, we can lead by example and prevent, or at least not contribute to, the societal frenzy of being stretched too thin.

Does “less but better” resonate with you? If so, don’t just see it as a personal goal to practice it; see it as a societal responsibility and a valuable investment in a world where we avoid unnecessary conflict by simply doing less—but better.

Danya Rumore, Ph.D., is the Director of the Environmental Dispute Resolution Program in the Wallace Stegner Center at the University of Utah. She is a Research Associate Professor in the S.J. Quinney College of Law and a Research Assistant Professor in the City and Metropolitan Planning Department at the University of Utah’s. She teaches about, practices, and conducts research on negotiation, dispute resolution, leadership, and collaborative problem solving.

Danya Rumore, Ph.D., is the Director of the Environmental Dispute Resolution Program in the Wallace Stegner Center at the University of Utah. She is a Research Associate Professor in the S.J. Quinney College of Law and a Research Assistant Professor in the City and Metropolitan Planning Department at the University of Utah’s. She teaches about, practices, and conducts research on negotiation, dispute resolution, leadership, and collaborative problem solving.