By Kelly Beck

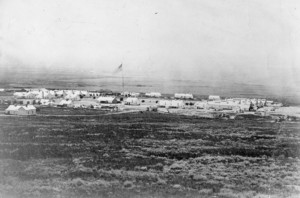

Today, Fort Douglas is home to the bustling student residences at the University of Utah. A university managed hotel and conference center occupies a portion of the fort, and the Fort Douglas Military Museum attracts Salt Lake City visitors. The well-manicured landscape of Fort Douglas today stands in stark contrast to this same location more than 150 years ago when Fort Douglas was established by Colonel Patrick E. Conner with a unit of infantry volunteers from California. With the Civil War raging to the east, western territories were left without military protection as regular army forces were sent to fight for the North. Secretary of War Simon Cameron ordered Governor John G. Downey of California to organize troops to protect communication and transportation lines between eastern and western states. So began Fort Douglas and Utah’s history in the American Civil War.

For much of the past year, a group of stakeholders, with a myriad of interests in historic Fort Douglas, have been meeting to develop a new set of protocols for the historic preservation of the fort. The stage was set for a successful collaboration in learning early on the primary interests for the fort with each stakeholder group and those also interested in the historic preservation. I facilitated this collaborative work group, and it was a perfect fit for my capstone project in the Environmental Dispute Resolution Program’s Short Course in Natural Resources Collaboration, which I participated in this last year for professional development.

Fort Douglas was first listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970 and then recognized for its significance to the nation’s history as a National Historic Landmark in 1975. During base realignment and closure proceedings, the fort closed as a military facility in 1990 and ownership then transferred to the University of Utah in 1992. The university now held the responsibility for managing the historic characteristics of the fort in accordance with the National Historic Preservation Act. Formal protocols for managing Fort Douglas as a historic property were established during the transfer; however, implementation of those protocols has proven to be challenging.

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

Not surprisingly, historic preservation isn’t the primary mission of the University of Utah, or the larger Fort Douglas-user community either. Rather, principal concern for historic preservation comes from outside the university and directed by provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act. This act established a State Historic Preservation Officer whose primary responsibility is to provide a voice for the state in historic preservation issues and requires inclusion of the public and non-profit organizations with historic preservation interests. A key step in forming workable preservation protocols is to move past organizational missions and positions to find underlying interests. Under ideal circumstances, a formal situation assessment would be conducted to summarize some of these key interests and to look for possible zones of agreement among those interests. Yet at Fort Douglas, the stakeholder group assembled before a situation assessment could be done.

During the first stakeholder workshop, we discussed the kinds of principles that should guide the management of the fort’s history. Through this facilitated conversation several guiding principles were discovered that garnered widespread agreement. Chief among these ideas was that historic preservation protocols should be proactive—that is, processes should be established that place consideration for historic preservation early in project planning instead of late during project implementation where preservation happens in response to an inadvertent discovery. Other important principles that solicited broad accord focused on the need for consistency in applying protocols and transparency in their enforcement.

I also interviewed many of the participants, asking each person what their interests were for the Fort Douglas and how those intersect with the university’s need to consider historic preservation. My interviews identified three major groups of common interests. First, interests associated with the Fort Douglas-user community emphasized the importance of their educational missions to ensure a safe and comfortable education experience for university students. Second, the university itself is likewise interested principally with the student experience, but also recognizes its role as the primary steward of historic Fort Douglas. And finally, the historic preservation community’s primary interests include maintaining the historic character of Fort Douglas and emphasized the importance of the fort as a public resource. What was common among all stakeholder groups was a desire to formulate historic preservation protocols that were clearly explained and could be incorporated easily into day-to-day functions of the fort.

Perhaps the most useful question I asked during my interviews was for each person to make their best guess at what the interests of the other stakeholders might be. For many this proved to be challenging, and on more than one occasion I was met with a response that was some variation of, “That’s a good question. I’ve never thought of that.” Once asked, though, the tone of subsequent conversation changed to revolve much more on interests, both personal and shared. By asking each participant to consider and express their thoughts about the interests of other stakeholders, I saw two important principles of mutual gains negotiation come to light. First, by considering that other stakeholders may indeed have legitimate interests different from their own, I watched as parties began to separate problems from people. Second, in asking each person to state what they thought the other party’s interests might be, it became considerably easier to move past positions to address deep interests.

Through these workshops and my interviews with key stakeholders, I uncovered a framework of shared interests that formed the foundation for collaboratively developing historic preservation protocols at Fort Douglas. Significant agreements about how the university considers the effects of future activities at the fort form the core of these protocols. But the commitments by all the stakeholders to form an ongoing user community council is perhaps the greatest testament to efforts at finding shared interests. The open conversations that we had between stakeholders who moved beyond fixed positions and worked to uncover shared interests are likely to serve each other best in the long run, and will work to manage a nationally important, public space that serves the needs of University of Utah students every day.

Bio: Dr. Kelly Beck is an archaeologist at SWCA Environmental Consultants in Salt Lake City. Over the years he’s found himself frequently involved in contentious projects with conflict between agency officials, project proponents, and the interested public. Dr. Beck is a proud member of the most recent graduate cohort of the Short Course on Natural Resources Collaboration through the Wallace Stegner Center’s Environmental Dispute Resolution Program.

Bio: Dr. Kelly Beck is an archaeologist at SWCA Environmental Consultants in Salt Lake City. Over the years he’s found himself frequently involved in contentious projects with conflict between agency officials, project proponents, and the interested public. Dr. Beck is a proud member of the most recent graduate cohort of the Short Course on Natural Resources Collaboration through the Wallace Stegner Center’s Environmental Dispute Resolution Program.