In 1947, Mohandas Gandhi declined a request to write an essay on human rights by responding, “I learnt from my illiterate but wise mother that all rights to be deserved and preserved came from duty well done.”

Gandhi’s mother’s wisdom illustrates a fundamental truism that underlies the nature of the common law over centuries of human experience. His insistence on duties as the correlative of rights is even more relevant today. “Rights talk” shapes the language and conceptualization of rights, ignoring or minimizing the role and function of duties.

This is the first in a series of posts that outline a larger project: The recapturing of the jural concept of duties as the inherent correlative of rights. This post introduces correlativity by addressing the “why” and “how” of the disappearance of correlativity as a fundamental jural concept, while the libertarian, as well as the law and economics and schools of jurisprudence, have gained predominance. It begins with an historical examination of the correlative role of duties in understanding rights. With the exception of discreet areas of the law, such as oil and gas and water law, express reference to correlativity of rights and duties has faded from legal doctrine; a fact, reflected both in its increasing absence in judicial opinions and the withering of the common law as a tool for addressing complex problems of the commons, such as environmental degradation.

The relevance of this history and its reflection in the common law is dense and heady stuff, especially for a blog post. However, the general lack of attention paid to correlativity requires an introduction that is approachable and somewhat conversational in the first instance. The why of why should I care about an obscure jural concept? goes to the heart of the problem in what is widely described as the “Tragedy of the Commons.”

The common law concept of correlativity is an essential tool for addressing the effective governance of the commons. It addresses the query of what constitutes a right, and is thus key to addressing the crises of the day: climate change, income distribution and the role of the state in democracies. For purposes of this project, I define “correlative rights” at the highest level of generalization as follows: As to all interests in things held in common by virtue of agreement, custom, legislation, or necessity, the right to a fair opportunity for enjoyment of the common incidents of ownership that encompasses a duty of non-impairment of those interests in other co-owners, which may be enforceable at common law, by injunction, damages, or by the terms of statutory regulation of the common thing.

The opening reference to Gandhi’s mother’s wisdom continued: “Thus the very right to live accrues to us only when we do the duty of citizenship of the world.” This was a consistent refrain dating back to his Hind Swaraj (1909), where he noted, “[T}he farce of everybody wanting and insisting on…rights, nobody thinking of…duty.”

Samuel Moyn, writing in the Boston Review, begins his essay Rights vs. Duties (2016) with these quotes from Gandhi. Moyn, a professor of both history and jurisprudence at Yale, notes the logical correspondence or “correlative“ nature of rights as dependent on duties to see that rights are “respected, protected, or fulfilled.” In laying the foundation for this project, I borrow heavily in this introduction from Moyn’s piece and commend the reader to read Moyn’s brief, but cogent, history of correlative rights and duties.

The fundamental relationship between rights and duties underlies an historical understanding about not only governmental obligations toward individual rights, but also of citizens toward each other. Despite the modern trend in law and philosophy to neglect duties when thinking about rights, it is in Moyn’s words,”[T]he centerpiece of ethical culture.” Certainly, it is of the essence of Judeo-Christian religious ethics.

Louis Henkin, widely recognized as the founder of human rights law, explained, “Judaism knows not rights but duties and at bottom, all duties are to God. (If every duty has a correlative right, the right must be said to be in God!)” Separate from religious sources of ethical culture is De Officiis, Cicero’s introductory text On Duties. Western ethics and philosophy education have treated Cicero as fundamental to an understanding of these topics for generations of students. Immanuel Kant, who laid the basis for morality on the capacity of people to exercise freedom in choosing their own ends, described the range of duties required for ethical living. Also, much of the common law, such as tort law, remains premised on this premodern focus on duties.

There is no shortage of reasons for a movement away from duties. Duties are both shield and sword. The medieval church and feudal system rested on an intricate network of duties that resulted in such a lack of individual rights for most humans that we refer to it as the Dark Ages. The Enlightenment is the response and corrective to a hierarchy that sacralized duties as a way of limiting the rights of the marginalized.

The history of rights and duties describes the ground on which today’s ideological battle over correlativity is fought. The difference between the Dark Ages and now is the way in which the correlative nature of each have been obfuscated by the present fetishization of individual rights as a way of limiting the rights of others in a shared or common society. The argument that the Enlightenment so freed us from the destructive properties of duties that we are best off doing away with them all together doesn’t make the correlative function of duties go away; it simply masks the gains of a different, rights-based hierarchy.

What are referred to now as classical or neo-liberal thinkers, often referred to as the Chicago School, drifted some distance away from liberalism as developed in 19th-century conceptions of rights and duties. As Moyn describes this period of liberal thought:

“First, they nestled their liberal political commitments within historical and sociological frameworks that made individual freedom a collective achievement that depended on ongoing collective commitments and necessarily common action. If liberals defended rights, it was not because they thought that individuals enjoyed perfect freedom in a mythical state of nature. Instead, rights, if plausible at all, were social entities—like everything else. The difference between good and bad states was not the distinction between those that respected the pre-political rights of the state of nature and those that did not. Rather, it was the difference between states that properly balanced social freedom with other collective purposes and those that did not.

Second, many liberals were concerned that when the state or globe was viewed as the forum for the protection of individual freedom alone, the result would be a destructive libertarianism that would sweep aside values other than individual liberty, including equality and fraternity. So their motivation to maintain the historic emphasis on duties in a liberal age was powerful. Despots had always droned on about the duties of subjects to the state. But even as libertarianism rose, some nineteenth-century liberals elaborated on the older republican idea that citizenship in a community of free people affords privileges but also incurs responsibilities.”

Placing the concept of duties within this liberal tradition, Moyn addresses what he calls the “false contrast between rights and utility.” Focusing on The Duties of Man (1860) by Giuseppe Mazzini, a work of global significance in its time and of Cosmopolitanism, Moyn demonstrates the centrality of human interdependence and duties as “the critical tool to immunize the individual liberty consecrated by rights theory from the libertarian heresy that he (Mazzini) found so destructive,”

Addressing the role of rights to the working-class, Mazzini wrote: “I do not ask you to renounce those rights, I merely say that such rights can only exist as a consequence of duties fulfilled, and that we must begin with the latter in order to achieve the former…Hence, when you hear those who preach the necessity of a social transformation declare that they can accomplish it by invoking only your rights, be grateful to them for their good intentions, but distrustful of the outcome.”

In Mazzini’s broad concept of duties, the interdependence of both the state, the individual and society requires a conscious balance between self-realization and communal obligation. Limiting the role of the state to protecting individuals from each other or their property risked the failure of a common human purpose greater than satisfaction of the ego. In this he castigated Bentham’s principle of utility as “recognizing no idea superior to the individual, no collective starting point, no providential education of the human race.”

Until relatively recently, Anglo-American liberalism embraced a robust role for duties in a framework of rights. Moyn cites T.H. Green’s fusion of “Evangelical religion, liberal politics, and Hegelian metaphysics” in Green’s Principles of Political Obligation (1885) as an example. This work challenged as myth Rousseau’s premise that the individual existed prior to, and in the absence of, society. The American legal realists Robert Hale and Karl Llewellyn directed their deconstructionist talents toward this misconception of prehuman rights, rather than as social goods created by society in service of society’s collective goals. While it is true that duties can be subject to the same metaphysical misconception, the goal of these liberal theorists was to recognize that if rights are innate, then so too must be duties in a world that seeks to justify market hierarchy and the values of social Darwinism.

With the rise of the law and economics school of legal doctrine and other libertarian doctrines in the last century, “rights talk” gained political and moral currency across the ideological spectrum. As noted in a humorous piece in the American Enterprise Institute, “We Are All Milton Keynesians Now,” the power of an ideology can swallow the arguments against it whole (American Enterprise Institute, February 10, 2020). It is the metaphysical power of a libertarian construct, the “free market,” which denies the social role of correlativity of rights and corresponding duties. This concept of the free market is quite different from the market as understood by Adam Smith. As Moyn’s outline of 19th-century liberal philosophy demonstrates, this present understanding of rights, which lacks a similar public language of duties, is an historical outlier.

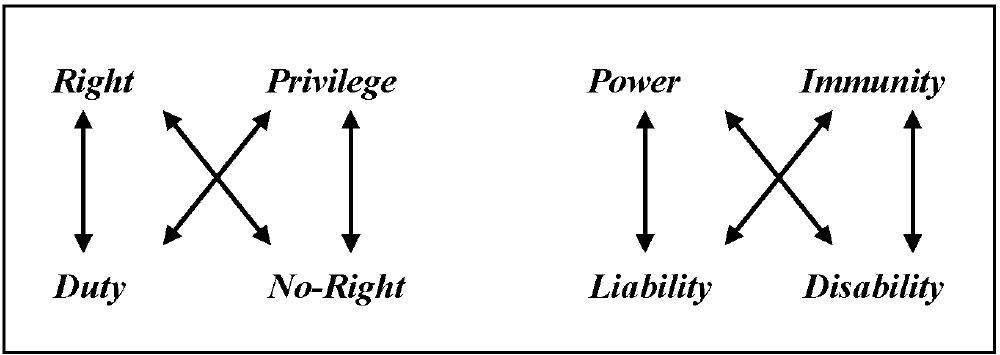

Fundamental to common law concepts of correlativity is the capacity of the law to distinguish between concepts whose differences matter. In 1913, Professor Hohfeld described what is now known as the “Hohfeldian” analytical structure, which separates out different legal relations by analyzing their opposites and correlatives. These include jural concepts such as privileges, powers and immunities, which are not rights per se, but related and separate concepts. When lesser or different interests are treated as rights, the capacity of society to address common concerns is limited. This is evident in the common law concept of waste, which protected both the present and future interests of others in things held in common. As clean water becomes scarce and climate change increases, the capacity of government to regulate individual interests in things held in common is particularly important. It is, in short, the common law concept of correlative rights and duties that provides a social and legal structure for governing the commons.

A concrete example of this concept of correlative rights and duties is fundamental to understanding modern oil and gas law. In 1899, the U.S. Supreme Court in Ohio Oil Company v. State of Indiana, 177 U.S. 190 (1899), upheld Indiana’s legislative power to regulate the production of oil and gas against a claim of takings in violation of the United States Constitution’s takings clause. The Court ruled that collective private owners of the oil and gas resource were protected in their privilege to reduce the oil and gas to possession by the governmental regulation of production methods; hence there was no taking of their rights in private property. The correlative rights of all the owners were conditioned or privileged based upon their duty not to commit waste of the common source of oil and gas.

The Ohio Oil court clearly recognized and called out the common law concept of the correlativity of rights and duties as a means of addressing governance of the commons, and it remains the law today. Moreover, there is nothing in the holding or its rationale that limits its applicability to oil and gas. Indeed, the decision is fundamental to the exercise of governmental authority to protect clean water, air, climate or ecosystems. It is why polluters of our common earth are not entitled to compensation when they are restrained from destroying the commons.

Although this post and the larger project to follow is intended as an introduction to the historical relevance of correlative rights and duties to governance of the commons in the context of Anglo-American common law, its implications are larger. Oil and gas law demonstrates the artificiality of treating resource law and environmental law as separate doctrinal entitles. Problems that arise from this are illustrated by many courts’ reticence to apply common law remedies where there is a claim of regulatory preemption. The global commons of which we are all a part and on which all our futures hinge is also implicated. For international law to be truly cosmopolitan in its reach calls for common human duties, which correspond to common human rights. Climate change, ocean acidification, sustainable ecosystems and food supplies are social problems that can only be addressed by balancing social ends and means. Governments and the rule of law are the mechanisms by which citizens of the world determine what they owe each other.

A conception of rights without reference to corresponding duties is ahistorical and incapable of sharing shared common resources.

Tom Mitchell is a Wallace Stegner Center fellow and practiced natural resource and environmental law for most of his 40 years as a practicing attorney. He also taught oil and gas law at the S.J. Quinney College of Law for 15 years. He joined the Law and Policy Program in 2021.

Tom Mitchell is a Wallace Stegner Center fellow and practiced natural resource and environmental law for most of his 40 years as a practicing attorney. He also taught oil and gas law at the S.J. Quinney College of Law for 15 years. He joined the Law and Policy Program in 2021.