By Dena Marshall for EDRBlog.org

Conflict mapping is a roll-up-your-sleeves pencil and paper exercise that I have come to appreciate and incorporate into my collaborative process practice and in my personal life. When conflict mapping is used as a tool for analyzing complex disputes it can be a great exercise for individual practice, training group exercise, and stakeholder engagement. The focus should be to identify the variety of stakeholders, their positions and interests, and the relationships between them. It becomes a dynamic stakeholder engagement mechanism to encourage people to roll up their sleeves, pull out pencils and paper, and start to look anew at conflict. In recent years, I’ve used conflict mapping with federal agency managers in Nevada, water professionals and banking executives in Bolivia, new mediators in Spain, and with my kids at home.

My first experience with conflict mapping was in a class taught by Dr. Todd Jarvis. At the whiteboard, he drew what looked like a gigantic bowl of spaghetti mush with circles and triangles, squares and stars connected with little squiggles, bold slashes, and zig-zags. Each geometric shape had a name inside representing stakeholders involved, such as the Department of Natural Resources, Ranchers, State Courts, Watershed Council 1, Salmon, Water, the Governor’s Advisor, and the Media to name a few. Every squiggly line carried some significance. Scribbled along some of the lines were statements punctuated as questions or exclamations. He called it the Spaghetti Western of conflict mapping, a tool for clarifying and bringing context to conflict.

I was doing my best to follow along and not lose track of anything, but by the end of the session I was thoroughly confused. What use would this spaghetti bowl of strings and shapes be to a mediator? To me, a few hours of background research, stakeholder interviews, and a walk in the room would have done the trick. As a result, I shied away from conflict mapping, preferring the comfort of my own high-touch approach. I was in conflict with conflict mapping!

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

However, during a family sabbatical to live in Cochabamba, Bolivia, I put conflict mapping to the test. I was invited to deliver a workshop in Water Conflict Management and Transformation to a group of seasoned water professionals; it was the first time the workshop would be delivered in South America. Cochabamba is the site of the famous Water Wars of 2000. I had studied the Water Wars at Oregon State University with Todd and Aaron Wolf and I was curious to meet the people involved, see the place, and find out how local control over water infrastructure fared over privatized management. In 2000, the communities of Cochabamba fought against water privatization and pushed a Bechtel subsidiary Aguas de Tunari out of Cochamba in favor of local water management. It was the subject of the 2010 film “Even the Rain.” When I arrived in 2016, more than half the City’s population still had no access to the municipal pipelines and must purchase untreated water from cistern trucks carrying water pumped from nearby private wells.

The participant group in the workshop consisted of twenty-five water professionals representing city, regional and national agencies, a journalist, two economists, one lawyer, three agronomists, a Watson fellow from the USA, university researchers, a representative of a global conservation advocacy group, and three people who had first hand knowledge of the 2000 Water Wars. It was an ideal array of perspectives in one room.

The participant group in the workshop consisted of twenty-five water professionals representing city, regional and national agencies, a journalist, two economists, one lawyer, three agronomists, a Watson fellow from the USA, university researchers, a representative of a global conservation advocacy group, and three people who had first hand knowledge of the 2000 Water Wars. It was an ideal array of perspectives in one room.

I introduced conflict mapping at the Cochabamba workshop as a tool for making sense of a live dispute. They were familiar with the 2000 Water Wars as the events shaped the course of history for Cochabamba, yet explosive conflicts over water remained. The group wanted to study a current dispute. They chose to apply the tool to its analysis of a local dispute over plans for a new dam in a nearby river. We arranged a field trip to four communities in a nearby watershed that would be impacted by a proposed dam on a local river: agriculturalists, tourist businesses, upstream users, and downstream users. The group divided into four teams. Each team conducted stakeholder interviews and then returned to the class to develop conflict maps. Their conflict maps became the foundation for a comprehensive report to the regional government with an assessment of the local conflict and potential impacts of the proposed dam.

Participants hunched over their tables shows the groups working with large sheets of paper, sticky notes and pens, to analyze the conflict from the perspectives of the stakeholder groups they interviewed. They incorporated local media coverage, photos, and their own personal knowledge to help populate the diagrams. As I observed this incredibly diverse selection of professionals, students, researchers, and advocates physically roll up their sleeves and put their heads together, I felt a palpable shift of energy in the room. People were talking to each other, arguing, laughing, listening, and thinking. This exercise, more than any other during the course of the workshop, delivered a transformative moment for the group. I was so wrapped up in the process, I forgot to take a photo of the conflict maps!

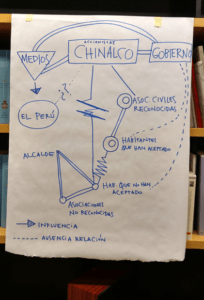

See below for what a conflict map can look like from a workshop conducted in Madrid, Spain analyzing a recent conflict in the Andean town of Morococha, Peru between the local indigenous community and a Chinese mining company Chinalco.

See below for what a conflict map can look like from a workshop conducted in Madrid, Spain analyzing a recent conflict in the Andean town of Morococha, Peru between the local indigenous community and a Chinese mining company Chinalco.

Conflict mapping is no spaghetti mush bowl. It need not be a complex process. The basic task is to identify the stakeholders, their interests and positions, and the relationships between them. Most important, and this piques the interest of journalists and activists, is to identify the hidden stakeholders. Who would be impacted by the changes but do not yet have a voice. In general I use the following “legend” to identify stakeholders, their positions and interests, and the relations between them.

| Conflict Mapping Legend | |

| Government entity | Rectangle |

| Private entity | Square |

| Social group – community | Circle |

| Media, courts (public purpose) | Triangle |

| Hidden stakeholder | Cloud |

| Strong alliance | Bold double line |

| Weak or neutral alliance | Single line |

| Tension / Conflict | Zig-zag line |

| Relationship uncertain or non-existent | Dotted line, question marks |

| Influence on a stakeholder | Arrow |

| Ruptured relationship | Broken line |

So try this at home and have fun with it. I use it often. Try it out on everyday conflicts like the neighbor’s encroaching shrubs, or water pricing, or choosing a restaurant, or fluoride in the municipal water source, or grazing practices. Use conflict mapping as an opportunity to open the discussion. Then call me when you get stuck.

Dena Marshall, JD, Cert. Water Conflict Management is a facilitator and public involvement specialist based in Portland, Oregon. In private practice for over 10 years, she specializes in issues related to water and community. She serves as advisor to the Program in Water Conflict Management and Transformation at Oregon State University, is Partner at Four Worlds Consulting, Principal of Marshall Mediation, and co-Founder of the global non-profit organization SwimTayka. Dena can be reached at dena@marshallmediation.net and 971-678-7043.

Dena Marshall, JD, Cert. Water Conflict Management is a facilitator and public involvement specialist based in Portland, Oregon. In private practice for over 10 years, she specializes in issues related to water and community. She serves as advisor to the Program in Water Conflict Management and Transformation at Oregon State University, is Partner at Four Worlds Consulting, Principal of Marshall Mediation, and co-Founder of the global non-profit organization SwimTayka. Dena can be reached at dena@marshallmediation.net and 971-678-7043.