By CK Miller for EDRBlog.org

It’s a lush forest scene: trees surround you, the ground is moist and spongy with moss, and above you stretches a seemingly endless canopy filled with lianas and vines. If I ask you to notice all the different green items in this environment, some would immediately pop out: such as the leaves on the trees, lichen on the trunks, mosses underfoot, and perhaps a frog or a preying mantis become visible. During this observation, you might identify twenty or more green things as your eyes become accustomed to spotting different shades and textures of green. Perhaps you anticipate a follow-up question about all the green things identified. But instead, I ask you how many brown things you specifically noted during your observation. You might feel disappointed; you weren’t looking for the brown. You were on-task, noticing the green.

It’s a lush forest scene: trees surround you, the ground is moist and spongy with moss, and above you stretches a seemingly endless canopy filled with lianas and vines. If I ask you to notice all the different green items in this environment, some would immediately pop out: such as the leaves on the trees, lichen on the trunks, mosses underfoot, and perhaps a frog or a preying mantis become visible. During this observation, you might identify twenty or more green things as your eyes become accustomed to spotting different shades and textures of green. Perhaps you anticipate a follow-up question about all the green things identified. But instead, I ask you how many brown things you specifically noted during your observation. You might feel disappointed; you weren’t looking for the brown. You were on-task, noticing the green.

What is the benefit of this exercise? There are two: 1) we will absolutely find more of the things we are actively engaged in looking for; and 2) this is a trade-off between the things we are and the things we are not actively looking for. We can apply this into many areas of life. When you are looking for ‘green,’ or say, solutions to the problem of community engagement, the brown (or another contingent variable) is less likely to pop out at you. You were able to expand your definition of green to allow more items to fit your search, to become a ‘green’ expert. In pedagogy, this visualization can help us to hone in on the concept of ‘selective attention.’ Learners, just like anyone in a rich environment, need pointers about what to pay attention to and what to dismiss.

‘Learner-centered teaching’: what is it?

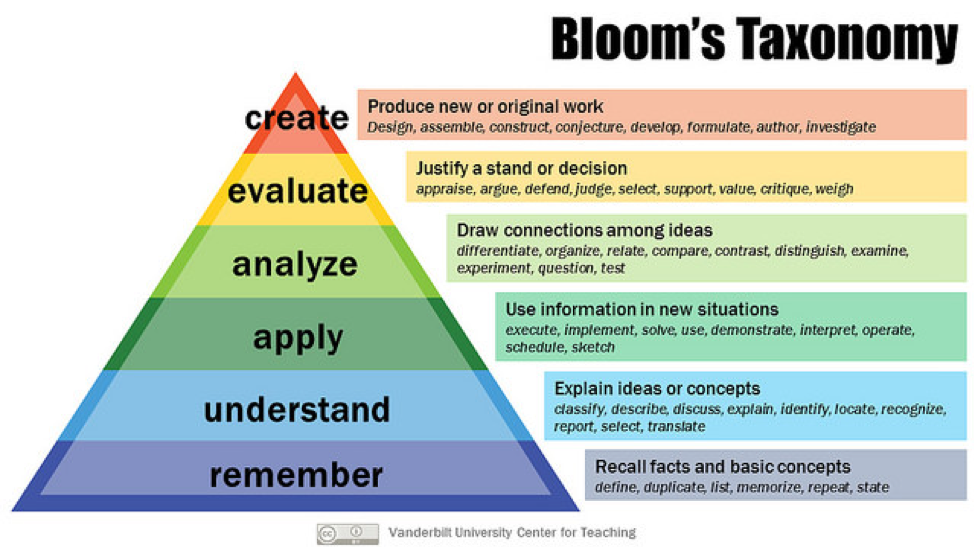

Learner-centered teaching engages students in every aspect of the learning process through active-learning activities, including being responsible for generating their own knowledge sources through collaboration with each other and with their communities. Learner-centered teaching is less about the learner absorbing what an instructor says and more about the student being able to demonstrate, analyze or apply a concept to a real-world situation. Learner-centered teaching is not a traditional “chalk and talk” or memorization and regurgitation.

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

How do we know what we are supposed to learn?

Learning-objectives provide a roadmap for student focus. When attempting to transmit information, it is important to acknowledge how learning will be assessed—e.g. will you be expected to identify the green items or the brown; or will you be asked to verify the change in the amount of green things at a later date? In the classroom, we aspire to provide transparency and reconcile expectations between content and assessment by providing learning objectives—specific action-oriented outcomes that identify what will be achieved at the end of instruction. For example: “At the end of this presentation, attendees should be able to evaluate the proposed pipeline in terms of the tax-burdens placed on local citizens.” Try using learning objectives when resolving a dispute with a family member—“When I’m done saying my piece, I’d like for you to be able to ______ your actions from my own.”

Learner-centered teaching is a collaborative process. A mediator’s work of defining respective parties desired outcomes is also a collaborative process—one that involves more teaching and learning than might be immediately visible. In mediation, participants can take the time to acknowledge that they have learning objectives and ways they will determine whether they have been understood. Merely attempting to express these objectives explicitly can help mediators align participants’ goals. It can save time, energy, and frustration in dispute resolution to first identify, not only goals, but actionable desires.

In an example, a presenter at a town hall tells listeners her learning objective: “At the end of this presentation, you should be able to compare and contrast the

funding methods of a given intervention.” She has explicitly identified something that every listener can achieve, without having to choose a side or tie themselves to a tree (yet). What a nice way to begin to resolve a dispute. Back to this concept of selective attention: when mediation begins by explicitly identifying (through action-oriented learning objectives) what participants can achieve that day or hour, the focus will be on accomplishment and collaboration!

Much of environmental dispute resolution (EDR) is combining in one place (e.g. a meeting room, a disputed site, a community center) individuals who are experts on one facet of the problem, and who must teach every other expert about their specific knowledge. Neuroscience research on how the brain learns identifies that transferring knowledge or skills to a new problem (a novel application of expertise) requires factual knowledge of the problems context and deep understanding of the structure of the problem. It is therefore very important, given what we know about applying expertise, that a deeper understanding be achieved, that experts learn to teach each other well, we encourage collaboration, and acknowledge a shared agenda.

Here are some more strategies for learner-centered teaching that can be incorporated into EDR practices:

- Focus on embodied learning: recent neuroscience research on the joint effort of “meaning making” uses ‘embodied’ cognition or embodied learning as a framework. Embodied learning indicates that not only are our minds engaged in the active process of making meaning, our physical bodies grapple with it too. In educational theories, this is complementary with the need for active learning activities—those that engage more than our auditory senses. For example:

- Formulate diverse, open-ended, types of questions for your audience when you develop a presentation. (Instead of ‘Any questions?,’ ask ‘What questions do you have?’)

- Try to modulate the sensory experiences of a presentation, vocally and visually.

- If possible, walk around while talking, ask participants to stand up, to shake hands with each other. Get them to interact, ask them to discreetly pass a note to someone across the room.

- Instigate emotional responses: ask attendees how a proposal makes them feel. Again, research shows that the emotional and learning parts of the brain are intertwined! During a learning experience, emotion and cognition operate in sync. Having emotions around others can help to bond a group. This is another way of learning from each other and can help speed the desire for a resolution, or hasten the collaborative process.

- Allow attendees to learn from each other: individuals are more likely to learn with others than to learn alone. Conduct the following exercise to promote peer-to-peer learning: split attendees in two, have one half work on a Pros list on a simplified version of a representative dispute, and the other half work on the Cons list.

In my own teaching experience when a heated topic is up for discussion, emotions will run high and sometimes cruel, extremist hypotheses come out. But I have found that learner-centered teaching helps the classroom stay on course. By giving students something to focus on, whether it be research or a learning objective etc., the students become more compassionate and collaborative with one another. Learner-centered teaching—at least in my classroom—takes us through conflict to comradery.

CK Miller is an PhD student in the Economics department at University of Utah and a Graduate Fellow at the Center for Teaching and Learning Excellence, where she uses her skills as a higher education teaching specialist to help a wide range of faculty improve their learner-centered teaching techniques. Miller’s research is on migration, gender and labor.

CK Miller is an PhD student in the Economics department at University of Utah and a Graduate Fellow at the Center for Teaching and Learning Excellence, where she uses her skills as a higher education teaching specialist to help a wide range of faculty improve their learner-centered teaching techniques. Miller’s research is on migration, gender and labor.