Born on the Navajo Nation reservation, it was several years before I became aware of the stark difference in resources available on the reservation versus off the reservation.

Born on the Navajo Nation reservation, it was several years before I became aware of the stark difference in resources available on the reservation versus off the reservation.

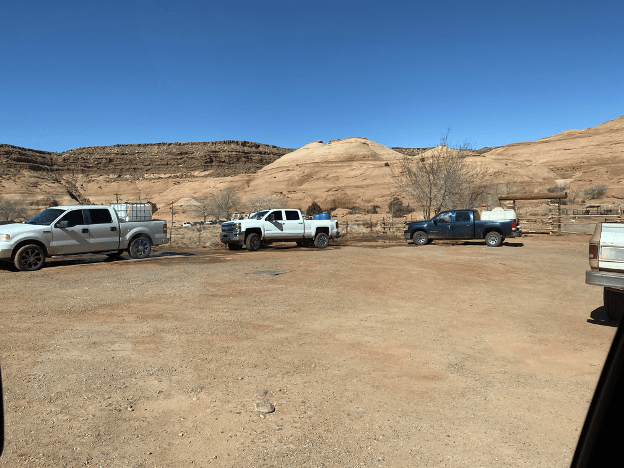

As a kid, my main concerns were outrunning the rez dogs chasing me on my way to school and hoping I had enough money to buy a pickle during recess. It wasn’t until later that I grew to appreciate the raw beauty of Diné Bikéyah—the sweeping desert landscape that always feels like home.

The Navajo reservation spans 27,425 square miles across southeastern Utah, northwestern New Mexico, and northeastern Arizona. Approximately 170,000 people reside there. And while I knew some of my relatives had to haul water to their homes, only recently did I realize water insecurity is not an American problem; it’s a Native American problem.

Around the time I started middle school, my father began working at the headquarters for Indian Health Service. The cross-country move to the greater Washington, D.C. area felt like I had been transported to a jungle—green was everywhere I looked. And water was abundant.

During the summer, we returned to the reservation to visit family and I noticed for the first time that we brought bottled water and food with us to save our relatives the expense of a long trip to the closest water source or grocery store.

If you are Navajo, chances are someone in your family is still hauling water today to meet their daily domestic needs. It’s a grueling and time-consuming process that can take all day for some families. It’s not surprising that Navajo families who rely on hauled water ration an average of seven gallons per day compared to the average American’s consumption of 100 gallons per day.

Many tribal homes do not have reliable access to water, with Native American households being 19 times more likely than white households to lack indoor plumbing. “This lack of access reflects historical and persisting racial inequities that have resulted in health and socioeconomic disparities.” Native Americans have the highest poverty rate, at 24.3%; they also have a lower life expectancy and suffer from a disproportionate disease burden.

In the West, water is critical to survival, both for individuals and communities. No one disputes that the Navajo Nation has tribal water rights sufficient to meet the purposes of its reservation, which includes being a permanent homeland. But the right to water is meaningless if you are not actually able to enforce those rights so that you can access and utilize that water. Indeed, despite being legally entitled to approximately 25% of the Colorado River water supply, many tribes in the Colorado River Basin are unable to fully exercise their water rights due to lack of infrastructure and other challenges. As a result, other water users have been using this water for decades without any sort of compensation to the tribes.

In the consolidated cases of Arizona v. Navajo Nation and Navajo Nation v. Department of Interior, the U.S. Supreme Court was asked to rectify this by finding the federal government has an enforceable duty—rooted in an 1868 treaty—to ensure the Navajo Nation has a permanent homeland. Navajo Nation claimed the United States is required to assess and plan for the tribe’s water needs to help ensure that their lands are livable. Several states opposed Navajo Nation’s position, arguing in part that the Basin is facing water shortages and there is not enough water to meet demand.

What does it mean to have a permanent homeland? The average American has probably never thought of that question. But, for many tribes, the answer is critical because it is what they were promised over a century ago by the United States, a promise they are still waiting to be fulfilled.

The federal government entered hundreds of treaties with tribes. In exchange for the acquiescence of millions of acres of tribal lands, among other things, the federal government made various promises to tribes. Sometimes treaty provisions protected the tribe’s hunting and fishing rights; in others, the United States agreed to provide doctors and teachers to meet the health and education needs of the tribe. In many treaties, establishment of a reservation as a permanent homeland for the tribe was a primary component.

Here, the federal government promised Navajo Nation a permanent homeland upon which future generations would prosper and agricultural development was feasible. But, on June 22, 2023, in a 5-4 decision the U.S. Supreme Court held that the United States is not required to take “affirmative steps” to secure water for the tribe.

In its 2020 decision, McGirt v. Oklahoma, the U.S. Supreme Court raised the hopes of Native Americans across the country when it held “the government to its word” and enforced treaty promises made to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, specifically the establishment of their reservation. Helping to assess and plan for Navajo Nation’s water needs is an implicit requirement to fulfilling that promise of a permanent homeland. And, as in McGirt, the federal government should have been held to its word.

But, broken federal promises are nothing new. The government itself has reported the many ways in which it has failed tribal nations. While the Arizona v. Navajo Nation decision is certainly a setback, tribes will continue to do what they have always done: to persevere in the face of injustice and continue fighting for their homeland.

Heather Tanana is a citizen of Navajo Nation and a former Assistant Professor of Law (Research) and Stegner Fellow at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law. She is currently a Visiting Professor at University of California—Irvine School of Law. Her research interests include addressing the wide gap in drinking water access for Native American communities.

Heather Tanana is a citizen of Navajo Nation and a former Assistant Professor of Law (Research) and Stegner Fellow at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law. She is currently a Visiting Professor at University of California—Irvine School of Law. Her research interests include addressing the wide gap in drinking water access for Native American communities.