Wallace Stegner, expressing his optimism about the future of the West, wrote: “One cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope.” This West is a construct, which like all human ideas relies on a shared capacity for common experience. This capacity relies on shared connections, which can be described as trust in a common bond, such as family ties, cultural continuums, and shared values. Equally significant is what this home of hope is not. It is not a zero-sum contest in which there must be a loser for there to be a victor. It is the opposite of leverage for parochial gain. A constant theme for Stegner was the failure of rugged individualism to solve challenges that require cooperation and compromise. A profoundly conservative moralist, Stegner stressed responsibility to a higher purpose than momentary pleasure or narrow self-interest. The creation of something new, like a state, or its education system where once there was none, involves bringing together disparate interests who sublimate their main chance to build something bigger than what would be without the communal effort. It succeeds, if at all, in fits and starts and by addition, not subtraction.

This post is an excerpt from a larger work-in-progress examining the history of the administration of Utah’s trust lands and the contexts in which that administration has been legitimately advanced and at other times impaired by non-trust considerations. The “Trust” as the term is used here refers to the legal fiduciary relationship of the state as the trustee of the “Trust Lands,” which it administers for the benefit of the beneficiaries named at the inception of the trust relationship at statehood.

The controversy

In March 2023, the federal government entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the state of Utah to exchange Utah’s lands held in trust within the newly restored Bears Ears National Monument for federal lands located elsewhere in the state. The exchanged federal lands selected by Utah’s statutorily designated trust administrator (SITLA) were chosen by the Trust to allow the Trust to monetize its lands and effectively manage them for their student and institutional beneficiaries across the entire state. The lands and mineral interests given up by the Trust are remote, difficult to manage, and have never generated meaningful returns to the Trust. However, at the end of the 2024 Utah legislative session, the legislature passed H.J.R. 26, which rejected Utah’s agreement for the exchange of these lands. In so doing, the legislature violated its duty as the trustee of an express trust for the benefit of all its beneficiaries, but especially the largest beneficiary group, Utah’s school children. This is a breach of an enforceable duty that requires the state to hold harmless the Trust against the loss of the benefit from the bargain for the land exchange.

The present controversy arises in the context of the geography of the Bears Ears. These two prominent peaks, visible from anywhere on Utah’s Cedar Mesa plateau and beyond, anchor the topography and cultural traditions of thousands of years of human history in the North American southwest. Numerous indigenous populations trace their ancestral origins to this landscape. The present Anglo population of San Juan County, Utah, descends from settlers who arrived in the area in conjunction with the United States’ displacement of indigenous populations on to reservations. The present San Juan County population, Anglo and tribal, now claims this landscape as their traditional homelands. The land, its archeological resources and life forms that populate its mesas and deeply incised canyons, form the backdrop for an ongoing story about the meaning of trust as that term is used to describe both legal fiduciary relationships and political relationships. This post focuses on the Utah Legislature’s most recent use of non-public trust lands as leverage for the benefit of the settler population of San Juan County, Utah, in response to the perceived result of the formal engagement by the federal government of the Five Nation Tribal Coalition in the NEPA scoping process for land management-planning for the Bears Ears National Monument (BENM).

Beginning with the passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906, 18 of 21 presidents of the United States have set aside lands with unique historic and cultural resources and landscapes. Nine Republican and nine Democratic presidents have used it to protect nearly 100 million acres onshore and many times that offshore. The Bears Ears National Monument was created under the authority of the Antiquities Act by President Obama toward the end of his second term, was diminished early in the Trump administration, and then reestablished by President Biden early in his administration. The state of Utah has opposed federal authority over federal public lands since the passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act in 1976 (FLPMA). While Utah is free to oppose or support federal land management decisions regarding the general welfare of the state and its own views regarding these federal actions, it is not free to disregard its obligations as the constitutional trustee and guarantor of the lands it holds in trust for the benefit of Utah’s public-school children. The history of trust land management demonstrates that pitting the interests of the Trust against the interests of the state as a whole is a false choice and a detrimental zero sum game.

1. Creation and administration of the school children’s trust

After many years of struggle with the federal government, the citizens of the Utah territory succeeded in gaining admission to the Union under the terms of the Utah Enabling Act of July 16, 1894. As with all other states entering the Union, Utah disclaimed any title to the federal lands within the state. As part of that bargain, Utah received lands under Section 6 of that Act, “Land Grant for Common Schools,” as well as other lands for specified purposes in Sections 8, 7, and 12 of the Act. Utah accepted these land grants in Article XX, Section 2 of Utah’s constitution as subject to an express trust for the “beneficiaries and purposes stated in the Enabling Act grants.” These are Utah trust lands, which are distinguished by the Utah state constitution from Utah public lands in Article XX, Section 1 of Utah’s constitution. Unlike Utah public lands, these lands have ever since been held as an express trust for the exclusive benefit of Utah’s school children and the other enumerated beneficiaries named in the Enabling Act. As with any trust relationship, the quality of the administration of the Trust is subject to the care and integrity of the trust administrators.

The first 100 years of administration of Utah’s trust lands can be summarized by two facts. The first is the disposal of roughly half of the 7 million acres of land granted to Utah for trust purposes. The second is the nearly empty coffers of the Trust’s permanent fund at the end of that period. There were several factors that played a role in this dismal performance, but the predominate factor was the decision to manage Utah trust lands like Utah public lands. This is well-illustrated by the legislature placing the Utah trust lands under the administration of Utah’s Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Sovereign Lands, which for years carried the responsibility for both of these very different types of lands. Public lands are held broadly for all of the people and the general welfare. Trust lands are not. The mixture of executive branch control of personnel and policy, coupled with the legislative treatment of both lands as subject to political forces, meant that other than separate bookkeeping for proceeds from trust lands, the implicit goal of the agency was to be responsive to those political forces. These forces were much the same as today: addressing rural economic opportunity; seeking leverage over federal lands policy; agricultural and livestock interests; and mineral extraction interests. While these same forces of economic activity are the source of revenue for the Trust, the purpose of the Trust is not to maximize private economic activity, but rather to generate a financial return to the Trust. The role of the trust land beneficiaries was honored not in terms of value returned to the Trust, but as a prop for arguments against federal land ownership and regulation.

Reform of trust land management began in 1989 with the very active involvement of the Utah PTA as a voice for the public school beneficiaries. The Utah PTA passed a resolution calling for an investigation of the Trust management and the history of marginal returns from the sale and management of trust lands. Between 1989 and 1994, the PTA pushed for audits and public review of what was required to reform management of the Trust, creating a powerful voice for reform in the legislature. Two of those years were spent revisiting the longstanding issue of checkerboard ownership patterns and obtaining appraisals to support the concept of exchanges as a way of improving the returns to the Trust from the portfolio of trust lands that made up the corpus of the Trust. In 1994, the Trust Lands Management Act was passed and codified as Utah Code §53C, resulting in the creation of a new entity, the School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA). The new independent agency represented a complete break with past practices with accountability to the beneficiaries and structured to limit the political forces whose interests diverged from those of the beneficiaries.

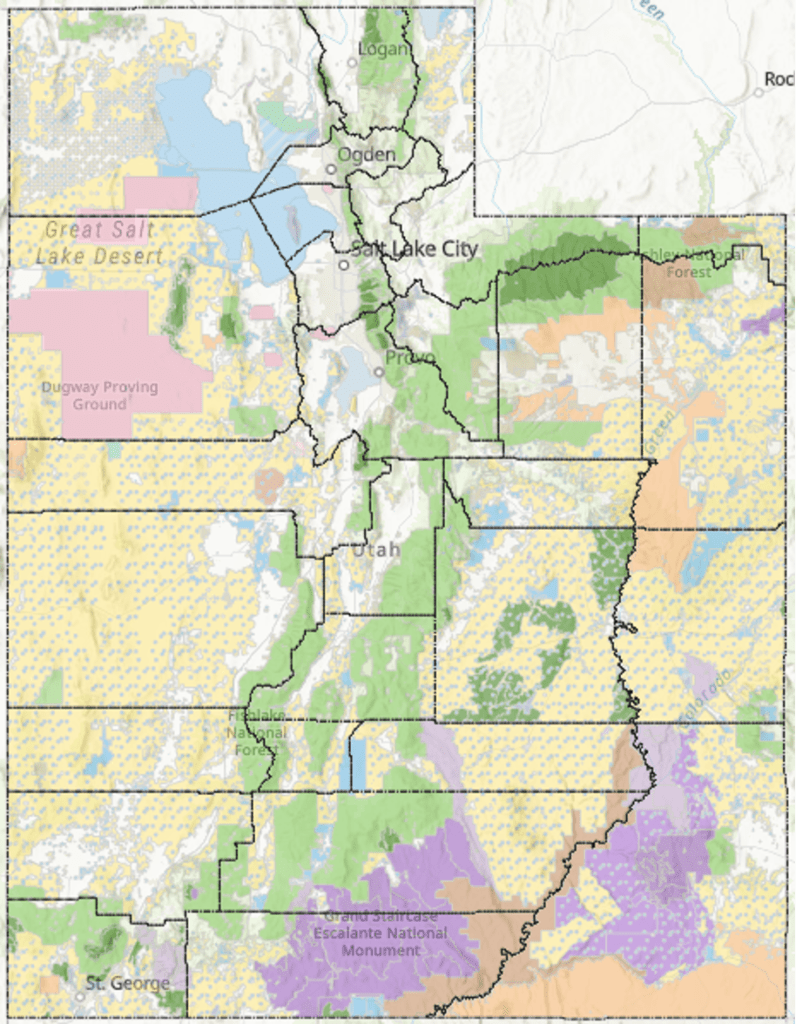

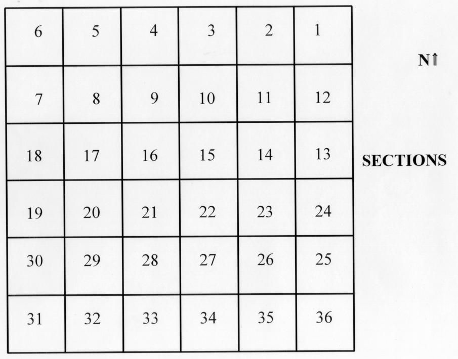

Political wrangling, however, has not been the only challenge to managing trust lands. The trust lands granted for the public schools consisted of four sections of land in every township that vested upon survey of the lands. A township has 36 sections. Each section is one square mile, or 640 acres in size. The four sections granted for the common schools in each township are numbered two, 16, 32, and 36. These and other Enabling Act land grants are, as a practical matter, random in terms of their topography, resource presence, and distance from roads or population centers. In addition, a section could not be located on the ground until after official survey, which in Utah was not completed until the middle of the last century. The figures below show the arrangement of the 36 sections in a township. The larger map of the state shows the checkerboard pattern of land ownership. The blue sections are Utah trust lands. A fully interactive version can be found with the relevant keys to identifying lands at the Utah Trust Lands Administration website. This method of survey and the resulting checkerboard pattern of land ownership is more complicated than this post can fully describe, but it has resulted in profound challenges to administering trust lands, public lands, private lands, tribal lands, and federal lands—thus, the need for exchanging lands to consolidate ownership around effective management goals and use of resources.

II. SITLA-administered exchanges and the national monuments

President Clinton’s Proclamation 6920, creating the Grand Staircase National Monument in 1996, supplied an opportunity for a solution that could address long-standing management challenges. Despite outrage by the state’s public officials over the new monument, it nonetheless provided the mechanism for addressing what had been an intractable problem. The newly constituted SITLA engaged in serious negotiations with then-Secretary Babbitt that culminated in an agreement in 1998 for a comprehensive land exchange package. The results were dramatic. That agreement exchanged 376,739 acres of trust land, including 176,699 acres within the new monument. Although the agreement was spurred by the monument’s creation, tens of thousands of additional acres of trust lands were removed from national parks, recreation areas, and other national monuments. Additional lands exchanged included 47,480 acres within Indian reservations, 70,000 acres in the Desert Range Experimental station and national forests, 2,560 acres of Kane County coal lands previously designated as unsuitable for mining, and mineral rights to 65,852 acres of trust lands. SITLA bargained for and received an immediate payment of $50 million mineral rights ownership in tracts of coal lands within coal-producing and active mining areas of over 160 million tons of coal and 185 billion cubic feet of coalbed methane in Emery and Carbon counties. The returns to the Trust were tremendous. The Trust also selected and received developable lands in Emery, Millard, Duchesne, Uintah, Washington, Kane, and Garfield counties. The large blocks of land in Washington County located next to new transportation infrastructure have been extremely profitable to the Trust. In addition to income from the coal lands already under lease, the coal lands included new coal leases and the bonus bids that came with that leasing activity. Both the federal land managers, the tribes, and the Trust gained management efficiencies and opportunities that had been foreclosed by the previous land-ownership patterns. Since this first agreement in 1998, and the exchanges of trust lands occasioned by that monument, the trust lands permanent fund grew from a few million dollars to over $3.2 billion. For example, the Drunkard’s Wash coalbed methane field alone has returned to the trust almost three quarters of $1 billion from the lands acquired in the Grand Staircase exchange. Additional exchange agreements have been undertaken since resulting in continued growth in the Trust’s permanent fund and millions of dollars available each year for the school children and the other beneficiaries. In short, where SITLA has been able to exercise its skill and care in structuring exchanges with the federal government, the Trust Land beneficiaries have benefited.

Controlling trust law

In Duchesne County v. State Tax Commission, 104 Utah 365, 371, 140 P.2d 335, 338 (1943) the Utah Supreme Court elaborated on the legal status of the Trust, holding that the Trust created by the Enabling Act and the Utah Constitution:

…[e]mbraces all the elements of an express trust, with the state [as] the trustee, holding title only for the purpose of executing the trust. . . The trust estate is definite, the trustee is certain, and the purpose of the trust and the use of the fund is definite, certain, and particularly characterized. This is sufficient. It must follow that the state holds the [school lands and the proceeds flowing from them] as a trustee of an express trust, limited in the amount, that can be expended, and the purposes and uses thereof.

In Nat’l Parks & Conservation Ass’n v. Bd. of State Lands, 869 P.2d 909 (1993), the Utah Supreme Court devoted much of its opinion to addressing the scope and nature of school trust lands. Beginning with the Utah Enabling Act and the Utah Constitution, the court reaffirmed the express nature of the Trust finding that this holding was consistent with other state and federal courts’ statement of the fiduciary duties imposed upon the state when administering school trust lands. Specifically, that the trustee has a duty to act only for the benefit of the beneficiaries and to exercise prudence and skill in such administration. The holding relies on the United States Supreme Court’s holding that the value of these lands, when they constitute a trust, cannot be used to further otherwise “legitimate governmental objectives, even if there is some indirect benefit to the public schools.” Ervien v. United States, 251 U.S. 41 (1919) In addition to citing binding federal precedent, the Utah Supreme Court surveyed other state’s cases addressing the lawful use of lands constituting school trust lands. Among the cases cited is State v. University of Alaska, 624 P.2d 807 (1981), which held that use of school trust land as a park for recreational purposes could not be upheld without the trust being compensated for the fair value of the lands. Citing the Eighth Circuit in United States v. Ervien, 246 F. 277 (8th Cir. 1917) for that court’s holding concerning the effect of the Enabling Act, the Utah Supreme Court stated the law in Utah to be: “in short, trust beneficiaries do not include the general public or other governmental institutions, and the trust is not to be administered for the general welfare of the state.”

That same limitation on the scope of who constitutes a beneficiary is reflected and reaffirmed in § 53C-1-102 of the Utah Code. This section of the code sets forth the purpose of the statute to provide for administration of the lands granted to the state for the common schools and acknowledges that the grant is accepted in the Utah constitution as a perpetual trust to which standard trust principles are applied. This statute expressly excludes as beneficiaries the public at large and the general welfare of the state. In other words, the legislature acknowledges that its acts regarding the trust are to be held to standard trust principles.

Because the Utah constitution (Utah constitution., art. X § 5(2)(d) ) appoints the state as trustee over these trust lands and provides that “[t]he State School fund shall be guaranteed by the state against loss or diversion,” the obligation of the state as trustee is to bear the costs of its administration that results in the loss or diversion of value to the trust. State v. Mathis, 2009 UT 85; 223 P.3d 1119 (2009).

III. The Utah legislature’s diversion of trust assets

On March 17, 2023, the state of Utah, SITLA, and the United States Department of Interior entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for an exchange of federal lands with trust lands. The parties agreed and recited that this exchange of trust lands within the boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument for federal lands located elsewhere within the state that are more suitable for revenue generation by SITLA would benefit both state and federal interests. Stating that the MOU would “further SITLA’s statutory duty to administer trust lands prudently and profitably for the exclusive benefit of Utah schoolchildren and other trust beneficiaries,” it was further acknowledged:

[T]he United States’ Lands and Mineral Interests referenced in paragraph three below were selected for acquisition by SITLA with recognition of environmental concerns and the values placed on them by tribal nations while avoiding significant wildlife resources, endangered species habitat, significant archeological, cultural, and historic resources, areas that are sacred or are traditionally, spiritually, or religiously significant to tribal nations, areas of critical environmental concern, coal resources requiring surface mining, wilderness study areas, and significant recreation areas. Consistent with these goals, this instrument is intended to avoid management conflicts with respect to lands and promote the objectives and legal mandates of both the United States and SITLA.

The MOU describes 167,013 acres of federal lands and mineral interests selected by SITLA to be exchanged for 162,510 acres of Utah State Trust lands and mineral interests, along with other realty interests located elsewhere in the state on which SITLA may maintain and issue rights of way for roads and other infrastructure. The agreement also provides for the retention of valid existing rights, including mineral, water, and grazing leases previously issued by SITLA to private parties on the lands given up in the new monument. The agreement also makes clear that it shall not be construed as a waiver or release of claims by the state or its subdivisions regarding the creation or modifications to the monument.

However, in 2019 the Utah Legislature had created §63L-2-201 of the Utah Code providing that prior to SITLA legally binding the state to an agreement to sell or transfer to the United States 500 or more acres of SITLA Lands, SITLA shall submit the agreement to the legislature for its approval or rejection. The sole apparent reason for this legislation was to exercise political will over Trust administration when it came to the United States. Then, on February 5, 2024, Governor Cox of Utah, a signatory of the MOU, exercised the termination clause in paragraph 8 of the MOU without comment or explanation. Finally, as the Utah Legislature ended the 2024 General Session a few weeks later, the House and Senate passed H.J.R. 26, a joint resolution rejecting exchange of school and institutional trust lands. HJR 26 rejected the MOU and the proposed Exchange Act of 2023 because, it recites, the “federal government has signaled that it will adopt an exceptionally restrictive and unreasonable land management plan that would negatively impact the communities surrounding the Monument and the state’s public school children, by restricting community access to grazing land, resource development, and recreation.” Additionally, the Utah Legislature resolved that: “the Legislature requires any land management plan put forth by the federal government or any other entity to be consistent with historical practice and benefit all local communities and trust land beneficiaries impacted by the proposed land exchange.” In other words, despite the recitals of the parties’ intent in signing the MOU, and the land planning process reflecting that intent, the legislature rejected the exchange in opposition to that intent.

The 2019 legislation under which the state acted in passing H.J.R. 26 ignores existing state law. Unlike the Utah constitution, or § 53C of the Utah Code which governs the administration of the Trust and trust lands, the 2019 legislation contains no criteria governing how or why the legislature shall determine whether to approve or reject an agreement to sell or exchange trust lands. However, Utah, as the trustee, remains subject to its own constitutional requirement to act only, as to the Trust, for the benefit of the beneficiaries. The trust principles made applicable to the state by the constitution do not allow the legislature to act in this matter, whether for the general welfare of the state or other public purposes in such a way that the benefits conferred by Congress in endowing the trust are diminished. The 2019 legislation fails to distinguish the purpose of trust lands from public lands, which are not subject to a trust and the Enabling Act.

The execution of the 2023 MOU reflected the state’s agreement that the Trust would be benefited financially by the exchange, as previously demonstrated by SITLA’s effective use of past exchange opportunities. The reasons enunciated by the legislature for rejecting the exchange demonstrate that its sought to further non-Trust purposes. Not only does the rejection of the exchange fail to satisfy the state’s fiduciary responsibility, but it also makes the pie smaller for all concerned. The rejection does not make the monument go away; it only harms the Trust. Utah law is clear that the trust lands are an express trust that must be administered for the sole benefit of its beneficiaries.

IV. Future actions

There are at least three possible paths forward. The first would be Utah legislation preserving the exchange and the value to the Trust contemplated by the MOU. The second is that the legislature could appropriate funds to reimburse the Trust for the value of the lost bargain because it believes that the value of traditional recreation activities on the trust lands within the BENM are worth the expenditure of public funds. Third, entities such as the beneficiaries, and others with a sufficient interest in the Trust and its administration, may bring litigation to enforce the obligations of the state as trustee to its beneficiaries. The school children, their representatives, guardians, and the citizens of the state of Utah have a sufficient interest in the administration of the trust lands to have standing to challenge legislative action that diverts or reduces the maximization of monetary returns to the Trust on behalf of its beneficiaries.

There is a long history in Utah—and the West generally—surrounding state, federal, and tribal relationships concerning lands and land use, especially in the context of state trust lands. This history involves many threads that require more time and space to unpack than a blog post can provide, but the nature of trusts and the principles of loyalty by the trustee to the beneficiaries are straightforward. The first chapters of the history of trust lands are a story of maladministration as Trust assets were treated like public lands. The resumption of legislative efforts to revisit this approach continues a past narrative that failed to bring hope or success for beneficiaries and the larger community of which we are all a part.

Tom Mitchell is a Wallace Stegner Center fellow and practiced natural resource and environmental law for most of his 40 years as a practicing attorney. He also taught oil and gas law at the S.J. Quinney College of Law for 15 years. He joined the Law and Policy Program in 2021.

Tom Mitchell is a Wallace Stegner Center fellow and practiced natural resource and environmental law for most of his 40 years as a practicing attorney. He also taught oil and gas law at the S.J. Quinney College of Law for 15 years. He joined the Law and Policy Program in 2021.